1950s

The beginning of the 1950s ushered in an era of moral panic that traversed the entire country. It began with Senator Joseph McCarthy's speech in West Virginia in 1950 in which he stated that there were hundreds of known Communists working within U.S. State Department. McCarthy and his supporters believed that these Communists were working to subvert the U.S. government and Democracy itself. McCarthy's persecution of alleged Communist sympathizers working throughout the federal government sparked a decades long policy of government purges of supposed disloyal federal employees that lasted well into the 1970s.1 Historians have dubbed this era as the Red Scare of the 1950s. But, in concurrence with the Red Scare was the Lavender Scare which saw hundreds of homosexual men and women being persecuted and dismissed from federal employment for being queer. Conservative politicians and the media linked the perceived moral failings of being queer with being susceptible or sympathetic to Communism and thus being anti-American.

Throughout the decade, newspapers across the country consistently covered the perceived problem of queer men and women, who worked in the State Department and other federal agencies, as being persons of "unconventional morality" whose "habits make them especially vulnerable to blackmail." There was a belief that their queer sexualities made them vulnerable to Communist manipulation. The media began to regard gays and lesbians as "undesirables," "moral risks," "moral weaklings," and "security risks."2 It was clear that many Americans would have believed that LGBTQ+ individuals were perverted, depraved, and untrustworthy and thus, had no place in American society. The feeling of exclusion would have been overwhelming for many queer folks.

With the national environment being so adverse towards LGBTQ+ folks, one would assume that queer men and women lived quiet lives attempting to hide their homosexuality. They may have perhaps retreated from public spaces and avoided any and all personal platonic, romantic, or sexual interactions. However, interestingly enough, that was not the case when we look at The Mid-Town Journal.

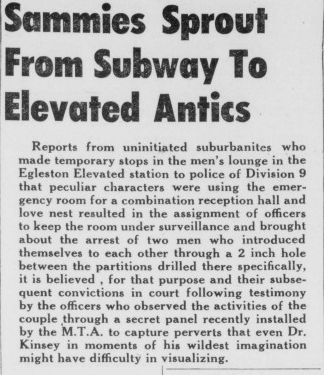

LGBTQ+ folks defied the national environment and continued to socialize and have causal sexual relations with other queer folks like they did a decade prior. The Mid-Town Journal reported at least two instances of small parties, hosted by gay men, being raided by the police during the 1950s. In 1951 alone, the journal reported on men having anonymous sex with each other in the bathrooms across the MBTA. For example, in February of 1951, police arrested two men at the Egleston station, which was located at the intersection of Columbus Avenue and Washington Street, for having sexual relations in a bathroom stall.3 Five years later, the police made a similar arrest of two men who were having sexual relations in a MBTA bathroom at the Arlington Street station.

The journal revealed how even in a national environment where gay men and women were viewed as morally corrupt and akin to Communist sympathizers, they did not waver in connecting with other queer folks. It was likely that they understood the risks in having sexual relations in precarious semi-public locations. Police often patrolled MBTA stations so their presence would have been known. Yet, gay men continued to use these spaces as opportunities for anonymous sex.

Subways were not the only locations where LGBTQ+ folks had sexual relations. All throughout Boston, similar to the 1940s, gay men and women found opportunities to connect with one another. Roughly, the same neighborhoods continued to be utilized for queer related activities. The Back Bay, South End and Beacon Hill and to an extent downtown Boston were popular spaces that appeared to be continually perceived as relatively safe enough to interact with gay men and women. This would indicate that the authorities did little to successfully suppress the activities of the LGBTQ+ subcultures. If they were successful, then queer folks would have moved to different parts of Boston. But, we do not see this in the data.

The map below showcases all the home addresses that were collected from The Mid-Town Journal between 1950 and 1959. What is noticeable about this map compared to its 1940s counterpart are the similarities, but also some of the slight differences. Firstly, we can see that the Back Bay, South End and Beacon Hill are areas where LGBTQ+ individuals continued to live. This would suggest that these locations were either still relatively affordable for queer men and women or that these neighborhoods continued to be fairly appealing and safe to live as a gay man or woman. In addition, we can also see that there are now a handful of individuals living in Roxbury, Cambridge and Charlestown. This is an outgrowth compared to the 1940s. We are seeing how the old three neighborhoods are no longer the only areas where queer men and women feel secure enough to live. It is possible that Roxbury, Cambridge and, to a lesser extent, Charlestown provided a more accepting environment for LGBTQ+ folks to live or that it was cheaper. But, with most arrests still occurring more towards downtown. We can assume that these outer neighborhoods were perhaps seen as places to live quietly and not necessarily places to be openly queer and socialize with other queer men and women.

Lastly, it should be noted that Frederick Shibley's many articles from the 1950s did not mimic the queer and communist discourse found in many other national newspapers. The articles that I found did not connect queer folks and their non-heterosexual activities with a communist conspiracy hiding in the backrooms or restrooms of Boston. Though, it should be noted that on occasion, Shibley would characterize gay men, lesbians or transgender women and their related sexual acts as peculiar or unnatural, but never as being subversive to Democracy or American society.

The most interesting finding from compiling and analyzing the data from The Mid-Town Journal from the 1950s is the noticeable uptick in the amount of transgender women who are mentioned and who are visible in Boston during this time period. As we can see from the graph above, there were 18 instances of trans women being reported in the journal compared to the nine that were mentioned from the 1940s. Why was there such a dramatic uptick between these two decades? One explanation could be the famous sex reassignment surgery that Christine Jorgensen, an American trans woman, underwent in 1952.

Christine Jorgensen became a national celebrity for embracing her transgender female identity and for being one of the first Americans to pursue sex reassignment surgery. Jorgensen's sex reassignment surgery "created a maelstrom of media attention and introduced many Americans to the concept of transsexuality." Throughout the 1950s, she appeared on dozens of talk shows and radio programs. Newsweek and Time frequently wrote about and interviewed Jorgensen.4 Without a doubt she was a celebrity and many Americans across the country would have become quite familiar with her and the story of her gender transformation. Thus, it is not hard to imagine the many transgender women of Boston, after reading about Jorgensen's journey, became confident in their own transgender identity and began to publicly present as female. Through The Mid-Town Journal this manifested as trans women walking down prominent streets such as Columbus Avenue or Massachusetts Avenue, occasionally soliciting sex from men in full feminine clothing or talking with inquisitive youths.5 Generally speaking, it is not hard to imagine the impact Jorgensen had on many young trans women. Her transition likely had a profound effect in encouraging other trans women to live their lives more openly than before.

Notes

[1] Johnson, The Lavender Scare, 4.

[2] Johnson, The Lavender Scare, 6-7.

[3] Frederick Shibley, "Sammies Sprout From Subway to Elevated Antics," The Mid-Town Journal, February 16, 1951, 1.

[4] Emily Skidmore, “Constructing the 'Good Transsexual': Christine Jorgensen, Whiteness, and Heteronormativity in the Mid-Twentieth-Century Press,” Feminist Studies 37, no. 2 (2011): 270.

[5] Frederick Shibley, "Mongrel Hair-Do & Economy Size Dogs Trip Slinky Siren," The Mid-Town Journal, February 29, 1952, 1.