General Findings

One of the many aims of this page is to highlight some important findings gathered from The Mid-Town Journal's entire twenty-eight year run publication. By using Datawrapper and ArcGIS, I will spotlight the demographic, gender, and sexual information of the queer individuals mentioned in the journal along with several maps that will draw attention to the varied residential and arrest locations of Boston's mid-twentieth century LGBTQ+ population.

Before we focus on displaying the data, it is important to address the accuracy and the veracity of The Mid-Town Journal. According to Frederick Shibley's daughter, only several individuals ran and operated The Mid-Town Journal. Frederick Shibley, his wife and a handful of other employees worked enough hours to publish this paper once a week. So, it was Shibley himself who wrote many of the articles, often attending court hearings at the Boston Municipal Court in order to write about the noteworthy crimes that had taken place throughout the week.1 This would suggest that the journal lacked the necessary resources to fact check its many articles and that Shibley may have exaggerated some of the details. After all, Russ Lopez, author of The Hub of the Gay Universe, does question the journal's reliability.2

But, there are two reasons why we should push back against Lopez's opinion. The first is that The History Project, a Boston based organization that archives and documents New England’s LGBTQ+ communities and authored Improper Bostonians, relies upon The Mid-Town Journal as a reputable enough source to include in their chronicling of Boston's queer subcultures. Improper Bostonians devotes nearly ten pages to the journal and Shibley's stories while also recounting how he was invaluable in publicizing the lives of queer Bostonians in a time where more traditional news outlets failed to do so.3 The Mid-Town Journal appeared to be trustworthy enough source to be used in Improper Bostonians without much reservations.

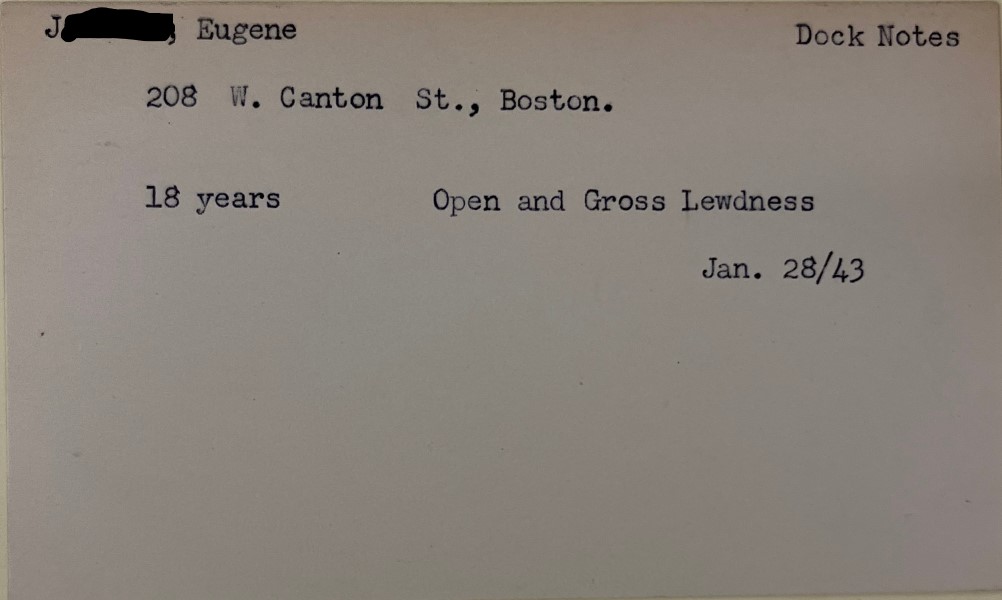

Additionally, I have been able to cross-reference multiple articles in the journal by using records from the Boston Municipal Central Court collection. These materials were created when the police arrested the queer men and women for a variety of crimes. The detainees would arrive in court the day after their arrest to either plead guilty or not guilty. The court would then document the name, age, home address, date of the criminal incident and the charge of most individuals. Comparing the court records with what is reported in The Mid-Town Journal, we can begin to understand the accuracy of the Shibley's articles.

Using over 50 of these index cards to cross-reference The Mid-Town Journal, I have concluded that over 90% of the demographic information, home addresses, and charges reported are accurate. In addition, nearly 100% of the names are correct as well. This accuracy rate is quite remarkable knowing the lack of resources available for Shibley and his handful of employees. We can conclude that The Mid-Town Journal can be used as a reputable source in collecting and analyzing the vast amount of information stated in this newspaper.

With the veracity of the journal established, let us begin to visualize and analyze the demographic and spatial information found within The Mid-Town Journal. The average age of a queer individual detailed in the journal was 26 years old. The youngest was 15 years old and the oldest was 65 years old. This suggests that the LGBTQ+ subcultures of Boston was quite youthful. This would align with previsouly stated information that World War Two mobilized and relocated a great amount of young folks into large cities for military training or for industry related employment opportunities. With the war ending in 1945, many of these queer men and women, returning from overseas, would have most likely remained in large metropolitan cities like Boston in order to be near other LGBTQ+ men and women. The mutual associations and connections that would have been built with other queer folks would have been a powerful incentive for gay men and women to remain in Boston after the war.

The graph above displays the genders of LGBTQ+ individuals found within The Mid-Town Journal from 1938 to 1966. What is noticeable is that the majority of the genders uncovered are those of cis-gender men with transgender females comprising about a third of data and finally cis-gender females constituting about a tenth. This would indicate that cis-gender gay men were quite comfortable in being active in the male homosexual subculture of Boston in the mid-twentieth century. Attending queer parties or searching for other men in subways or in city alleys highlights the confidence these men had in being relatively open with their sexualities even knowing the risks it brought in being arrested by the police for 'unnatural acts' or lewdness.

Transgender women make up a considerably bulk of the data. The transgender subculture was almost as large as the homosexual subculture. Often, the transgender women mentioned in The Mid-Town Journal were arrested for either soliciting sex along major intersections of the South End or were arrested in cafés and bars. Police frequented certain dining establishments along Columbus Avenue arresting any one participating in same-sex sexual relations or presenting as someone of the opposite sex. Like their cis-gender male counterparts, many transgender females were brazen in their desires to present as women day or night, on the streets or in the cafés.

Lastly, cis-gender females were the smallest group that was recorded. We should not conclude that Boston lacked a sizeable lesbian subculture. Afterall, men and women make up an equal share of the population. One way to interpret this data is that society permitted women to form close and intimate relationships amongst themselves which acted as an cover for more sexual and romantic relations to form. Police officers could have easily interpreted the close relationships between women as simply platonic female friendships rather than anything more intimate. Another possible interpretation is that women did not feel as comfortable , compared to men, in using public spaces as a means to connect with other queer women.

As we can see, the sexualities decoded from The Mid-Town Journal closely parallel the genders associated with LGBTQ+ activities. It is important to note that the journal never used any of these sexual identifiers when detailing these individuals. Regardless, we can attach specific sexual identities onto these folks as a way to understand the queer subcultures of Boston and to make the data intelligible. To simplify, homosexuality is to be associated with cis-gender males while cis-gender females are lesbians and transgender females are to be categorized as queer due to their fluid gendered characteristics and physicality.

Overall, this data reveals the enormity of the LGBTQ+ subcultures that existed in Boston during the middle twentieth century. It is clear that gay men and transgender women appeared to be those who were the most audacious in going out into the city and socializing and having sexual relations with other gay men and transgender women. Subsequently, this also meant that they were highly visible groups for the police to track, surveil and arrest. The police were familiar with certain bars, cafés, motorways and subway restrooms that quickly became quintessential queer meeting spots. The lack of representation among lesbians would suggest that either the police paid little to no attention to their romantic and sexual exploits and thus, lesbians largely evaded the historical record or that lesbians of this era participated in less risky public exploits which would significantly decrease detection from the authorities.

To a certain extent, these graphs show us the visibility of certain LGBTQ+ subcultures. The Mid-Town Journal divulged crucial demographic information, but it also reported on the home addresses and arrest locations of queer men and women. This spatial information is important in understanding where LGBTQ+ folks felt the most comfortable living. Furthermore, a map showing the arrest locations will highlight where queer folks ventured to meet and socialize with other queer men and women.

This map is crucial in understanding what neighborhoods of Boston were popular places for LGTBQ+ folks to reside. As the map shows, the South End, Beacon Hill, Roxbury, and Back Bay were the four main neighborhoods where queer folks congregated the most. The close proximity of all the neighborhoods to each other and to downtown suggests that Boston proper was affordable and relatively welcoming enough for LGBTQ+ individuals to live, work and socialize.

The graph above features certain details that the map fails to make clear. For example, with this graph we can see that there were certain queer folks who lived well beyond the city lines of Boston. Some folks lived as far away as Watertown, Fitchburg, Brockton, and Worcester. Others lived across states lines. One person lived in Manchester, New Hampshire. Others lived in Lewiston, Maine and New York City. This suggests that queer individuals, who lived outside of Boston, often traveled moderately to long distances in order to mingle with other like minded gay men and women which indicates that Boston may have had the reputation for being the center of LGBTQ+ intrigue and allure for New Englanders.

The map above showcases all the arrest locations gathered from The Mid-Town Journal from 1938 to 1966. What is noteworthy with this map is that all the arrests are generally confined to Boston in three major areas: Back Bay, South End and around downtown. East Boston, Charlestown, Cambridge and Somerville are absent while Roxbury, location for many home addresses was only mentioned once. But why are those highly populated areas not mentioned? One possible hypothesis is that the Back Bay, South End and downtown were well established localities where LGBTQ+ subcultures felt reasonably safe to associate freely. This would again indicate that for many queer folks living in and around the Boston metropolitan area, it would have been known that to socialize with other queer individuals, one only needed to be no more than a 15 to 30 minuet walk from Boston Common to stumble across a gay bar in Scollay Square or a queer friendly café along Columbus Avenue.

The aim of this page was to give a macro analysis of the data that I compiled from the entire run of The Mid-Town Journal. There are a few general conclusions we can make about the metadata. The first being that homosexual men and transgender women were the most chronicled LGBTQ+ subculture in Boston during the twentieth century. This would suggest that gay men and queer trans women were rather confident in their abilities to socialize in public areas regardless of the watchful eyes of the Boston police department. Lesbians did frequent gay bars and cafés like their queer brothers, but were most likely able to intermingle openly under the guise of close platonic female friendship which the police would have been unconcerned with.

Furthermore, South End, Back Bay, Roxbury and Beacon Hill were the four most desired locations for LGBTQ+ folks to live. Relatively low rent prices, proximity to a MBTA subway station, or the benefits of living next to queer and welcoming neighbors could explain why these particular spaces were popular for queer folks to reside. Regardless of their rationale, many queer men and women did not travel far from their homes to socialize with other queer folks. The locations of their arrests, being within walking distance of many of their homes, suggests that there was a great amount of overlap between where one lived and where one socialized. If you live in proximity to other LGBTQ+ people, then why travel far to fraternize with them? These neighborhoods would have already been familiar areas with well known establishments that tolerated queer folks. Thus, what most likely happened was a self-sustaining cycle occurred where queer men and women moved to queer neighborhoods and remained in order to be close to other queer folks which, in turn, attracted even more queer men and women and so on. Before you know it, LGBTQ+ men and women all across New England knew where to live and associate with other gay men and women.

Notes

[1] Penelope Shibley, Email message to Sam Hurwitz, March 3, 2021.

[2] Lopez, The Hub of the Gay Universe, 133.

[3] Improper Bostonians, 148.