Traveling Back: Understanding the Roots

For those who are unfamilar with this clip, it's from the 2015 film The Big Short. Starring Brad Pitt, Steve Carell, Ryan Gosling, and Christian Bale, the movie is based off of the 2010 nonfiction The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine by Michael Lewis. The film follows a group of investors who, realizing how unstable and corrupt the housing bubble is, decide to bet against the U.S. mortgage market. They make millions of dollars in the process but, as the above clip shows, do so a terrible cost as the true extent of the economic collapse becomes clear.

This page explores the longer-term roots of the 2008 financial collapse and both how and why such disasters. are central issues to reproductive justice, which as we know from the previous page are profoundly shaped by race, gender, class, and even marital status. In the introduction of A Dream Foreclosed, author Laura Gottesdiener reflects on a striking difference that she noticed in people's peceptions of the foreclosure crisis as she traveled around the country interviewing those experiencing housing instability. Although a bit long, I decided that it's worthwhile to include in its entirety:

White Americans often spoke about foreclosure as a singular, shocking event. Many blamed relatively recent changes in the U.S. economic structure, such as lending deregulation, the stagnation of middle-class wages or the development of the securitization process, which mortgage-pushing companies and Wall Street used to cash in on predatory, often unpayable loans. In contrast, African Americans rarely spoke about foreclosure as if it were something new and unprecendented, or even something that only affected mortgage-holding families. Instead, they tied today's housing crisis to a longer fight for home - one that encompasses hundreds of years and includes everyone from families who pay mortgages to people who live in public housing. Most strikingly, they often proposed far more visionary economic and social solutions, sometimes even questioning the very fundamental structure of housing in America. When I [Gottesdiener] mentioned my observations to Max Rameau, co-founder of the national housing network Take Back the Land, he agreed: 'White people see this as a foreclosure problem. Black communities see this as part of a historic pattern of disenfranchisement,' he said.1

"A historic pattern of disenfranchisement." While this statement is sad, it also isn't at all surprising. There cannot be reproductive justice without housing justice, and in the following paragraphs I will argue that the 2008 financial crisis got its start two decades before Goldman Sachs, J.P Morgan Chase, Bank of America, and the Lehman Brothers brought the global economy down with them.

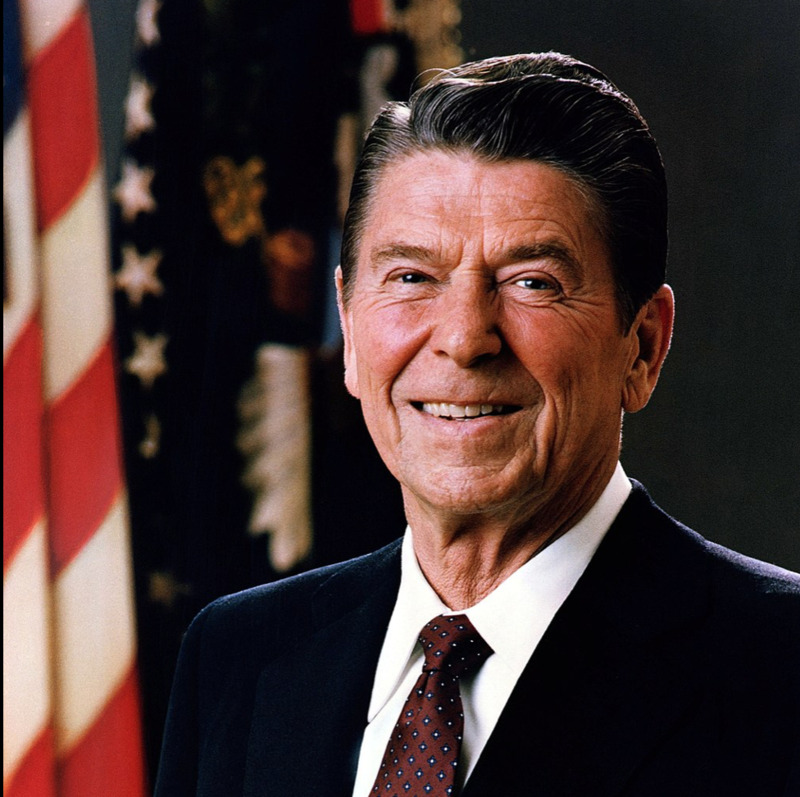

Growing up, Ronald Reagan seemed like a pretty cool guy. Although he was never talked about in my high school history classes all that much, from what I knew about his presidency he sounded fairly innocuous, almost boring. Now that I'm in graduate school studying American history, the story is much more complex and, depending on your perspective, darker.

The 40th president from 1981-1989, Ronald Reagan's administration led one of the most zealous campaigns to reduce social support for children, the elderly, and anyone receiving what was derisively known as "welfare." Laura Briggs writes that the Reagan administration cut resources for reproductive labor by "dramatically reducing the availability of low-income housing" and ending programs for children and the elderly.2

Throughout his tenure as president, Ronald Reagan's administration successfully eroded not only public opinion for welfare, but made it that much harder for anyone to actually apply for benefits or even want them. Thus, the twin attacks on both reproductive care and stable housing created tremendously difficult living and working conditions for low-income people and families. Following the mid-1970s recession and stagnation of wages, the resurgence of welfare "reform" only "pushed mothers into low-wage work at a time when the value of the minimum wage was declining steeply." Briggs reports that, in constant dollars, minimum wage hit its high point in 1968 but by 1989 it was worth 40% less.3 It became increasingly difficult to afford basic necessities like food and rent, much less childcare or healthcare.

With all of this in mind, how could poor, predominately single mothers possibly keep up and make ends meet? The answer is, of course, that they couldn't, especially as the 1980s bled into the 1990s and President Bill Clinton infamously promised to "end welfare as we know it." Sociologist Charles Murray furthered negative public opinion that welfare mothers were draining the country of its resources with his 1984 Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950-1980. He argued that Aid to Familis with Dependent Children (AFDC, another name for welfare) was "itself causing poverty by rewarding female-headed households and should be eliminated." Despite the fact that AFDC helped a broad diversity of people including widowed and divorced women, those leaving abusive relationships, and people with disabilities, there were few politicians who couldn't do away with it fast enough. 4

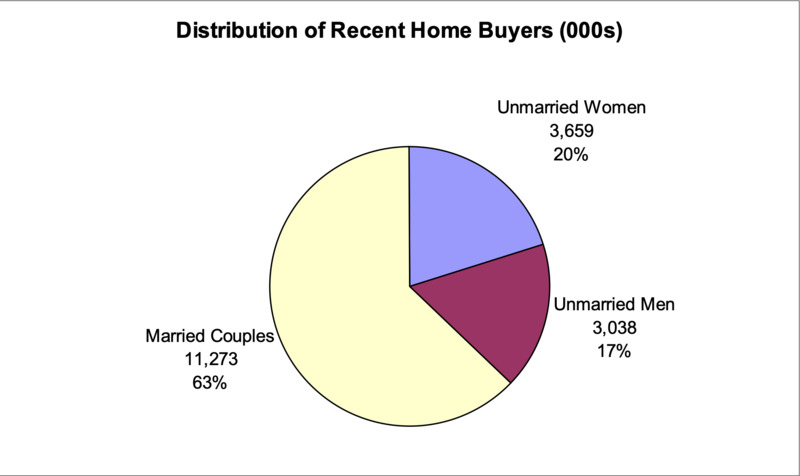

The above graphs are taken from Rachel Drew's illuminating 2006 study published by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University. Although these are only two data visualizations, Drew explains how their statistical breakdown actually tells us quite a lot about the abudance of unmarried women in the housing market in the early 2000s. In 1995, single female homebuyers represented only 14 percent of the housing market, but by 2003 that number jumped to 21 pecent. Unmarried female homebuyers purchased over $550 billion worth of real estate alone between 2000-2003, and Drew also found that, when segmented by age, "minorities account[ed] for nearly 30 percent of female buyers under 45, relative to only 22 and 24 percent of unmarried men married couples, respectively." Notably, Drew writes immediately after that "large numbers of minority signle mothers likely influence this trend" (as figure one shows).5

Alone these numbers aren't inherently alarming; indeed, they can even look like cause for celebration. And in one way, they should have been. That the numbers of unmarried, single women, and single mothers were fast becoming one of the largest segments of the housing market should have been a sign that gender inequities were starting to shrink, even as I've no doubts that there were cases where individuals and families didn't get hosed and remained financially solvent. But when looked at as a piece of a larger whole following the market crash, those statistics seem less like cause for celebration and more like early warning signs that had been festering for decades.

And so the unstable financial melting pot was born. It isn't a coincidence that as thousands of already vulnerable people were forced off of welfare and into "workfare" programs, "risky loan originations skyrocketed by 900 percent, eclipsing the establised prime market." In her article "Eroding the Wealth of Women," Amy Baker clearly connects this massive increase of risky lending to the "legislative shifts within economic policy and housing that allowed for the development of new types of lenders, market risk, competition, and mortgage products." Thus, years before the turn of the century, the beginning of the end of the United States housing market had already begun. The erosion of welfare, affordable housing, educational support, and childcare during the 1980s was simply where it all began. 6

End Notes

[1] Laura Gottesdiener, A Dream Foreclosed, 7-8. Emphasis my own.

[2] Briggs, How All Politics Became Reproductive Politics, 47.

[3] Briggs, How All Politics Became Reproductive Politics, 49.

[4] Briggs, How All Politics Became Reproductive Politics, 53.

[5] Rachel Drew, "Buying for Themselves: An Analyss of Unmarried Female Homebuyers," Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, June 2006, 4-7.

[6] Baker, "Eroding the Wealth of Women," 61. I recongize that the attacks on welfare, or at least the contemporary disdain of welfare, began earlier than the 1980s. However, I decided to begin my story during the early 1980s as it was during President Reagan's administration that the practical dismantling of welfare began in earnest.