Black Women's Labor

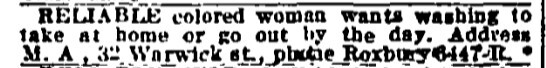

Race has always played a role in work in the United States. The kind of work available to you, the ways you were able to complete that work, and how your community viewed the work you did, all intersect with race. The end of the plantation system of slavery in the Southern US did not fundamentally change how Americans thought about race. Whether in the North or South, race continued to be a factor in what kinds of work were available to any individual, as well as how much they were paid for it.

Gender, similarly, has also always been a factor in labor. “Women’s work” has taken various forms throughout US history, often being separated from men’s work by arbitrary cultural factors and societal limitations. Women’s work has also been historically undervalued and underpaid in comparison to traditionally male occupations. Work is also not limited to paid jobs outside the home. Domestic work within one’s household is a form of work, though rarely recognized as such.

The federal census recorded the self-reported occupations of individuals, including their role within the household and what kind of work they did. Although there is no perfect measure of the accuracy of census data, such reports are in many cases as close to self-description of how these women saw their work as we may be able to get, particularly for Black women, whose presence in the historical record is often limited.

The census records of 1920 reveal a time of increased independence for women and changing social and cultural conditions within the US at large. The expectations and conditions of life and work for Black women, however, were much more curtailed than their white counterparts.

This is not a complete record of Black women’s census responses in 1920 Boston, but this representative sample of women between the ages of 20-30 can help shed some light on what possibilities of work were possible for Black women. The stories of individual women included here, though filtered through official records and government data, can hopefully give the readers some insight into the lives of these women and the cultural norms that shaped their work opportunities.