What are "Coptic" Textiles?

The textiles and textile fragments in the Tellalian Collection are beautiful, diverse, colorful, and ambiguous. Floral, animal, human, and abstract motifs contribute to what is ultimately an iconographical cornucopia, and the Collection represents the visual culture of late antique and early medieval Egypt at its absolute finest.

Fortunately, the Tellalian Collection is not the only surviving set of textiles from this period. Significant collections exist at global museums such as the Louvre in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, as well as scholarly institutions such as Dumbarton Oaks. These “Coptic” textiles are objects that came from clothing, tapestries, burial shrouds, and many other kinds of decorative pieces.

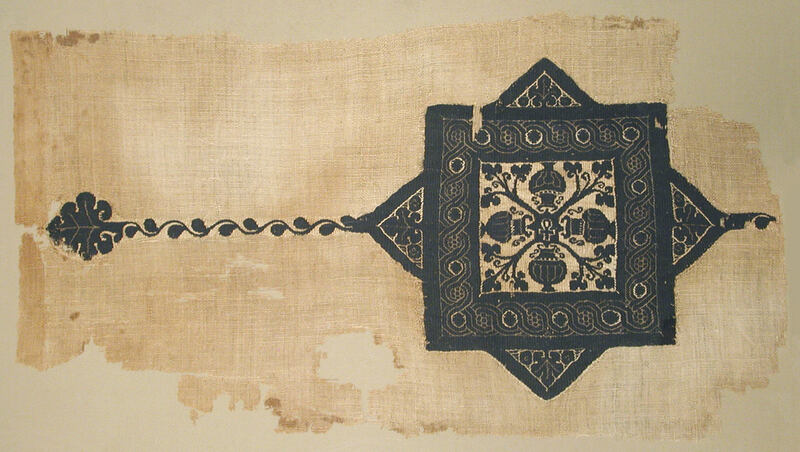

Richly Decorated Tunic

c. 660-870

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public Domain

As Vasileios Marinis observes, such artistic output was the “product of intermingling civilizations, an expression of the cultural diversity of Egypt at the time of their production.”[1] When considering such a collision of worlds, how can we begin to categorize these extraordinary objects?

Traditional sources (and even some contemporary ones) tend to use the adjective “Coptic” to describe all Egyptian textiles from the period (c. fourth-tenth centuries). Ann M. Nicgorski aptly sums up the history of the term:

The term ‘Coptic’ derives from the pharaonic name for the city of Memphis (the house of the Ka of Ptah) via the ancient Greek name for Egypt, Aegyptos, which was abbreviated in Arabic as qibt. This was the word used by the Arab conquerors of Egypt after 641 CE to refer to the entire non-Muslim population, which at that time was mostly Christian. Thus, the word ‘Copt’ has come to denote Egyptian Christians, while the adjective ‘Coptic’ may be used to describe various historical and contemporary manifestations of their culture, such as language and visual art.[2]

In other words, “Coptic” is an ethno-religious-linguistic adjective denoting historical and contemporary Egyptian Christians: Coptic people, adherents of Coptic Christianity, speak the Coptic language. As Nicgorski notes, this terminology is inaccurate because the material and visual culture of the period—especially as reflected on textiles—often cannot be clearly associated with just one ethnicity or one religion.[3]

Garment Fragment with Trees and Birds

6th-7th century

Walters Art Museum

Creative Commons

Still, many sources still lump all late Roman, early Byzantine, and even some early Islamic Egyptian art under this unifying “Coptic” framework. At the same time, there exists a tendency to see “Coptic” art as an entirely separate phenomenon from the Roman, Byzantine, and Muslim worlds in which it arose. It has likewise been dismissed as some combination of decadence, decline, or folk art.[4] Fortunately, recent scholarship has corrected this (often Orientalist) judgement. Instead, scholars such as Nicgorski recognize objects such as the Tellalian textiles as “an organic part of general stylistic trends seen in many other regions of the late Roman and early Byzantine Mediterranean.”[5]

Far from being a backwater, late ancient and early medieval Egypt was, in many ways, the center of the Afro-Eurasian world. It had been ruled by Hellenized Macedonian descendants of Alexander the Great’s generals until the Roman annexation in 30 BCE, before being inherited by the eastern, and later Byzantine, empire. Later, the region was an early conquest of the successive Islamic Caliphates that arose in the mid-seventh century. Although far from the independent polity it had been during the times of the pharaohs, Egypt played a historically central role in all of these Mediterranean empires, proving grain and other agricultural output to the empires in which it endured.

Coptic Textile Fragment

late 3rd-5th century

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public Domain

This position arose from this centrality. We might easily imagine a tunic’s woven-in apotropaic knot—such as McMullen 2018.12—as having been knit by a pagan devotee of the god Serapis, for a Christian patron’s tunic, and worn as protection by that person’s Muslim descendants a couple generations later.[6]

Tapestry with Apotropaic Knot

5th century

McMullen Museum of Art

Public Domain

In the Tellalian Collection, many symbols displaying religious and regional characteristics also coexist with each other within this dynamic visual vocabulary. As Nicgorski observes, the textiles contain not just Egyptian, Greek, and Roman characteristics but also Persian, Syrian, and Armenian elements.[7] Of early Christian Egyptians specifically, Marinis recalls how the community “inherited a mixed tradition, laden with Greek, Roman, and pre-Christian images, which was woven in every thread of everyday life, from tunics to pottery, from utensils to lamps.”[8] In the Tellalian Collection, crosses and evangelical symbols are just as common as Heracles and Tyche. Bacchic grapevines can be found next to animal motifs. Rabbits representing fecundity are right at home among vegetal motifs of prosperity.[9] Tunics, tapestries, tablecloths, curtains, and their fragments share this ambiguity.

As Amandine Mérat observes, by Egypt’s eleventh and twelfth centuries “everyday clothes for Christians, Jews, and Muslims were basically the same,” with differences arising not from religion or culture, but from socioeconomic standing.[10] In Egypt, we can see a millennium of sartorial syncretism in which iconographical trends transcended demarcations of ethnicity and religion. The objects in the Tellalian Collection exemplify this milieu of multicultural coexistence, and mutual influence.

Tapestry Band with Stylized Birds

7th century

McMullen Museum of Art

Public Domain

[1] Vasileios Marinis, “Wearing the Bible: An Early Christian Tunic with New Testament Scenes,” Journal of Coptic Studies 9 (2007): 96.

[2] Ann M. Nicgorski, “The Fate of Serapis: A Paradigm for Transformations in the Culture and Art of Late Roman Egypt,” in Roman in the Provinces: Art on the Periphery of Empire, ed. Lisa R. Brody and Gail L. Hoffman (Boston College: McMullen Museum of Art, distributed by the University of Chicago Press, 2014), 163n.22.

[3] Nicgorski, “The Fate of Serapis,” 157.

[4] Nicgorski, “The Fate of Serapis,” 163-164n.24.

[5] Nicgorski, “The Fate of Serapis,” 157.

[6] The apotropaic knot reflects “an inventive combination of motifs that is probably related to contemporary eye-shaped amulets intended to thwart the evil eye. See Nicgorski, “The Fate of Serapis,” 159-160. For Nicgorski’s brief list of exemplary references to other similar ornaments, see 165n.40.

[7] Nicgorski, “The Fate of Serapis,” 157.

[8] Marinis, “Wearing the Bible,” 96.

[9] Nicgorski, “The Fate of Serapis,” 157-158.

[10] Amandine Mérat, “Clothing and Soft Furnishings,” in Egypt: Faith after the Pharaohs, ed. Cäcilia Fluck, Gisela Helmecke, and Elizabeth R. O’Connell (London: British Museum Press, 2015), 214–21.