in Christ Church, Boston

Overview

Christ Church (Old North Church) was the second oldest Church of England (Anglican) church founded in Boston1. As the city’s oldest Anglican congregation, King’s Chapel, began to outgrow their space, members began a subscription campaign to raise funds for a new church in 1722. The first stone was laid on April 15th, 1723, and Reverend Dr. Timothy Culter led the first public service on December 29th of that year. The Capturing Space project seeks to recreate this historical space and thus explore questions about the impact of built landscapes on the human person. It is therefore useful to consider the sensory experience of attending Christ Church in the colonial era and how differences of racial and social status amidst congregants may have changed their experiences of the building. From its earliest days, Christ Church served a broad selection of Boston’s population, both wealthy merchants as well the enslaved and those living in poverty. Some of these divisions were reinforced by church participation, while others were subtly challenged.

Seating Types

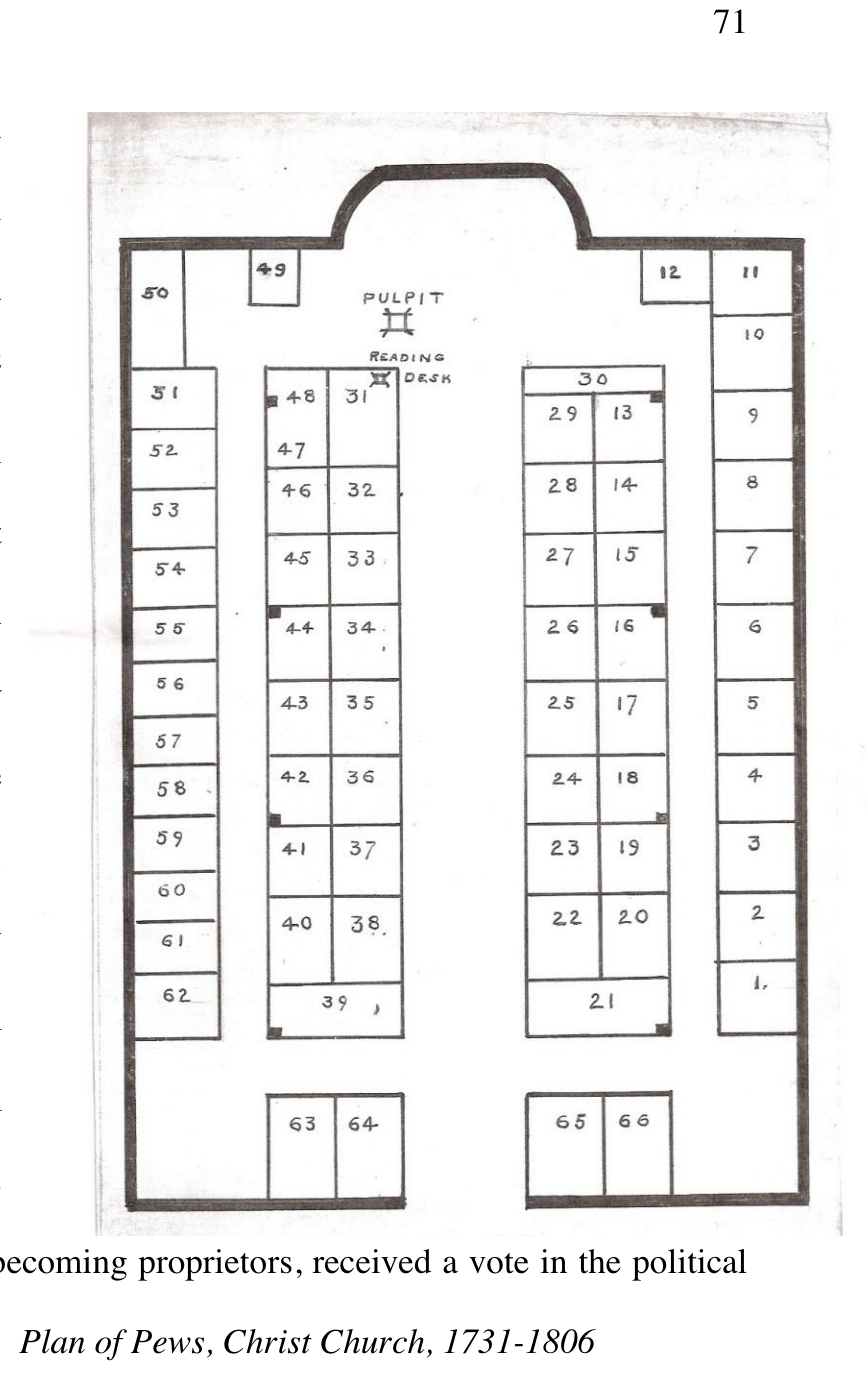

Originally, Christ Church had four types of seating arrangements for attendees, box pews, free seats, the gallery, and standing room.

Box Pews

The majority of seats were box pews, seating that was restricted to parishioners who purchased the right to that particular pew. Christ Church was a new foundation, lacking an endowment, and selling pews was a way to establish the financial health of the church.2 The vestry sold the rights to each box pew, charging thirty pounds for one on the ground floor and twenty for one on the upper level. Once someone owned a pew, they were expected to offer a “contribution” each week to the church, and the vestry retained the right to take back a pew if someone fell behind on their contributions.3 Additionally, each year Christ Church collected a tax from pew owners. In return, box pew owners were guaranteed seats, were spared close physical contact with unfamiliar people, had added protection from the cold, could customize the interior of their pew to their own tastes and comfort levels, and became voting members or proprietors, in the church. Only proprietors could buy or build a tomb under the church. Women could own pews, and sometimes poorer individuals would band together to purchase a pew. While wealth limited who was able to initially purchase a pew and where, those with higher social status seemed to have gotten an earlier choice of which pew to purchase. The center-aisle pew was reserved for “Strangers and Wardens,” allowing for visitors and interested members to see for themselves the best Christ Church could offer. Box pews remained at Christ Church until 1806, when they were replaced with slip pews, which could fit more people. Parishioners continued to purchase pews at Christ Church until the early twentieth century.

Free Seats and Standing Room

Free seats, or back seats were the name for the unadorned benches that ran on the outside walls of the sanctuary. These were seats for those who could not pay for a pew but who could still give some weekly money. These congregants could still receive communion, the central sacrament of the Sunday liturgy, and participated in services, although their view was obstructed. Benches at the back of the upper gallery could not see the service. Since these seats were not purchased, there was no guarantee of obtaining one. If all the benches were full, only standing room remained.

Race and Seating

Adding race as a consideration modifies our understanding of the gallery seating. While Christ Church was predominantly white, and all the listed pew owners in the colonial era were white, Christ Church had the highest proportion of black congregants, both free and enslaved, of any Anglican church in Boston in the eighteenth century. By 1727 there were 32 “negroe and Indian slaves” in the parish, as its founding minister, Rev. Dr. Timothy Cutler recorded in a letter.4 Cutler himself owned slaves.5 Whether accompanying their owners to church or attending of their own volition, black and indigenous individuals most likely sat in the free seats of the galleries. As stated these seats had the worst visibility, and the gallery itself was the least desirable seating as it was subject to more extreme temperature changes. At other Anglican churches in Boston, black individuals sat in the aisles, but there is no record of this happening at Christ Church, and indeed, the vestry expressly charged the sexton to “keep ye rails to the Altar clear from Boys & Negroes sitting there” and to “take care that no disturbance happen by the boys or any other unruly persons in the gallery as also within the Church limits during divine services.”6

As much as seating divided parishioners, there were moments in the service when these divisions broke down. The celebration of communion was allowed to any baptized member. Elite parishioners were likely to partake, and walking forward to receive offered a chance to show off their finery, but Cutler did also give communion to black congregants. At the communion rail they knelt side by side. As Ross Newton notes, “in a culture where shared drinking vessels forged communal values with groups of men, drinking from a common precious vessel left an impression, especially on poor and enslaved communicants, who all other times were absent or ignored.”7

Visual Landscape

The visual experience of attending Christ Church in the colonial era was more involved than the congregational (Puritan) meeting houses that dominated Boston. In 1737 John Gibb Jr., the son of the founding vestry member John Gibbs Sr and his wife Mary Gibbs, the proprietors for pew eight, painted the loft with “6 Cherubims heads with festoons,” and painted the gallery to replicate cedar wood, which had biblical connections to Solomon’s Temple.9 Around this time, the churched added panels to the Chancel with the Ten Commandments written on them, adorned with cherubs and done up in gilt. Above the chancel was the text, “THIS IS NONE OTHER THAN THE HOUSE OF GOD, AND THIS IS THE GATE OF HEAVEN.”10 Pictures from the turn of the 20th century show painted ceilings, but it is unclear if these were part of the original design. Beginning in 1727, the church would have been decorated with greens for Christmas, which was a controversial theological statement in the context of Puritan New England. The four angels decorating the organ were gifts of Captain Thomas Grunchy, the proprietor of Pew Twenty-Five, who captured them from a French ship in 1746 during King George’s War.11 A silver communion service, usually covered on the altar with a red damask cloth, and a silver baptismal bowl would also have engaged the eyes.

Anglican churches and aesthetic sensibilities in the eighteenth century stressed proportion, regularity, and symmetry over sheer ornamentation. In the words of a sermon preached by Henry Caner at King’s Chapel in 1749, “Our worship is grave and comely ‘tis pure and simple yet full of noble majesty not superstitiously encumberd nor indecently naked. Let every circumstance attending it partake of the same genuine and native ornament. Let the house of God in which it is perform’d rise up with the same majestic simplicity neither encumber’d with vain and trifling decorations nor yet wanting in that native grandure [sic] which becomes the beauty of holiness and which tends to beget impressions of awe and reverence in all that shall approach it.”12

Soundscapes

The audible experience of attending a service at Christ Church before 1776 would have been dominated by three things: the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, the Psalter of Tate of Brady, and the sermon.

Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer provided the liturgical structure for type of each service and the appropriate scriptural readings, collects, and prayers for each Sunday of the year. Originally developed by Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cramner in 1549, the BCP underwent various revisions. The 1662 revision, which is what Christ Church’s first parishioners would have used, was instituted after the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in England and remains in use today in lightly adapted form. Worship services following the BCP involve a high amount of congregational participation, for example in the form of call and response sections and communal recitation of creeds. The repetitive nature of each Sunday service allowed even illiterate members the chance to participate in worship.13 The BCP was a distinctive mark of Anglican worship, much critiqued by the Congregational majority of New England. Prayer books were expensive, highly desired items that had to be imported from England.

Here is a link to a 1693 printing of the prayer book. If interested in recording any parts of the prayer book, I recommend using a collect or part of the service for administering holy communion.14

The Psalter of Tate and Brady

The Psalter of Tate and Brady is the second factor influencing the soundscapes of Christ Church. This Psalter provided loose translations of the Psalms with accompanying music. Corporate singing was another distinguishing mark of Anglican worship; Congregationalists generally allowed for instrumental music and organ music specifically at home, but not a part of worship services until end of the eighteenth century.15 Christ Church obtained its first organ in 1736, and the current organ dates to 1759. The organ and later, the church bells, both cultivated a sense of “awe and reverence,” integral to Anglican worship.16

Here is a link to the 1698 revised edition of the Psalter, the edition likely used by the early members of Christ Church. At the back are some of the tunes.

Here is a Youtube video of Tate and Brady’s rendition of Psalm 51, sung to a sixteenth-century tune, Southwell.

The Sermon

Finally, the sermon constitutes the third major aural experience of attending Christ Church. The preacher relied on the strength of his voice and the sounding board above the pulpit to fill the space and reach listeners even at the back of the upper gallery of the church. Here is a link to a funeral sermon delivered by Reverend Dr. Cutler, the first priest of Christ Church, given at the church on November 28th, 1734 for John and Elizabeth Nelson.17

Notes

- While today Christ Church is Episcopalian, that denomination only formed after the American Revolution necessitated a break with the authority of the Church of England. In colonial America, Anglican churches were those led by clergy ordained by Church of England bishops and that used The Book of Common Prayer to structure their services.

- This arrangement was far less common in England, where churches tended to be older, until the nineteenth century. J. C. Bennett, “How Formal Anglican Pew-Renting Worked in Practice, 1800–1950,” The Journal of Ecclesiastical History 68, no. 4 (October 2017): 767-8.

- This could take a while to happen; Captain Newark Jackson, who purchased pew thirteen in 1738, died in debt in 1743. His widow Amey struggled financially but was listed as the owner until the church reclaimed the pew in 1769. The Old North Church & Historic Site. “This Old Pew: #13 – Capt. Newark Jackson,” January 23, 2020. https://www.oldnorth.com/blog/capt-newark-jackson/.

- Quoted in Christ Church, Salem Street, Boston, 1723. Boston: Christ Church, 1918.

- The Old North Church & Historic Site. “This Old Pew: #27 - Reverend Dr. Timothy Cutler,” May 23, 2022. https://www.oldnorth.com/blog/this-old-pew-27-rev-timothy-cutler/.

- Ross A. Newton, “Patron, Politics, and Pews: Boston Anglicans and the Shaping of the Anglo-Atlantic, 1686-1805.” Ph.D., Northeastern University. Accessed June 6, 2023. ProQuest.

- Newton, “patron, Politics, and Pews,” 129.

- Newton, “Patron, Politics, and Pews,” 71.

- Newton, “Patron, Politics, and Pews,” 124; Amy Budge, “This Old Pew: #8 - Mary Gibbs.” The Old North Church & Historic Site, October 20, 2020. https://www.oldnorth.com/blog/mary-gibbs/.

- Quoted in Newton, “Patron, Politics, and Pews,” 124.

- The Old North Church & Historic Site. “This Old Pew: #25 - Captain Thomas Gruchy,” March 21, 2022. https://www.oldnorth.com/blog/this-old-pew-25-thomas-gruchy/. Quoted in Newton, “Patron, Politics, and Pews,” 126.

- Newton, “Patron, Politics, and Pews,” 50.

- The book of common prayer and administration of the sacraments and other rites and ceremonies of the Church according to the use of the Church of England : together with the Psalter, or Psalms of David, pointed as they are to be sung or said in churches, and the form and manner of making, ordaining, and consecrating of bishops, priests and deacons. Church of England. London: Printed by Charles Bill and the executrix of Thomas Newcomb, deceas'd ..., MDCXCIII [1693], UMich.

- Newton, “Patron, Politics, and Pews,” 47-8.

- Newton, “Patron, Poltics, and Pews,” 126.

- Timothy Cutler, The final peace, security & happiness of the upright. A sermon deliver'd at Christ-Church in Boston Novemb. 28. 1734. On occasion of the death of John Nelson, Esq; which was on the 15th of that month. And of Mrs. Elizabeth Nelson his consort, which was the 25th of Octobe preceeding. By Timothy Cutler, D.D, Printed by J. Draper, 1735. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, Gale. Accessed 29 June 2023.