South End Tenement

Home Life

For immigrants arriving in Boston around the turn of the 20th century, life in the city was far different from what they’d experienced at home. Expectations in food production and preparation, laundry, work, and habits of living had to be adjusted. In turn, Boston itself changed, as immigrant populations transformed the city’s physical and cultural landscape.

Commercial food products were on the rise between 1880 and 1920, offering new and easily consumable packaged foods in cardboard or tin cans. While immigrants made food familiar from their homelands, they also were inundated with advertising from brands offering products purported to provide nutritional and medicinal benefits. In the Boston Pilot, a newspaper which served the Irish immigrant population, ads abound for products like Bell’s Seasoning, Ivory Soap (for the bath, toilet, and fine laundry), Jell-O Ice Cream Powder, and Dr. Haines’ Golden Specific, intended to be placed in the food or coffee of those who consumed alcohol excessively to curb their drinking - not necessarily with their knowledge.

Mass-produced products extended beyond groceries, however. Grover & Barker’s sewing machine received significant advertising space in the Boston Pilot, indicating the popularity of such technology in tenement houses. While making work like sewing easier, the pervasive presence of such machines speak to the tenement’s dual purpose as a place of work and domestic life.

For many women who lived in tenement housing, “keeping house” included constant labor looking after their families and sometimes earning additional income through their skills. Items like sewing machines often meant greater volumes of work could be accomplished, rather than representing a transition to a more leisurely lifestyle.

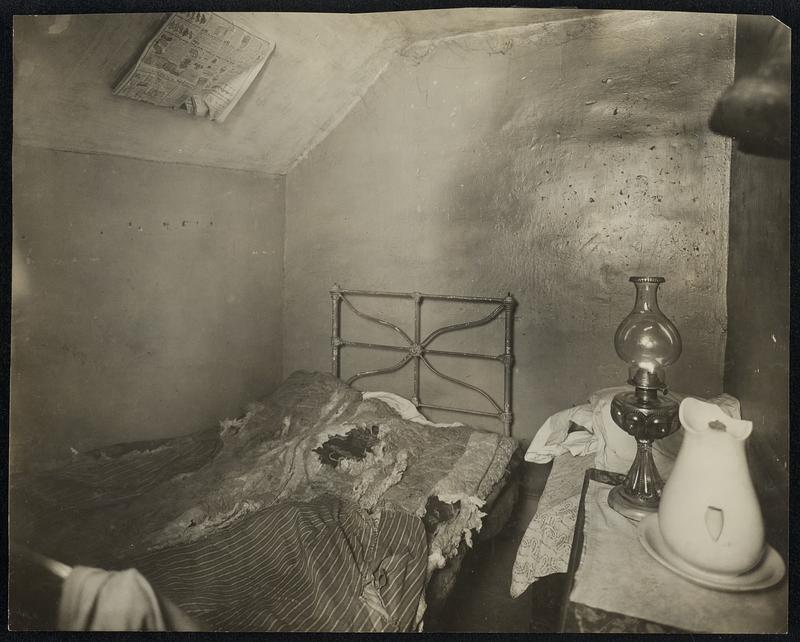

Life in a tenement could indeed be quite challenging. Government reports for the city of Boston give us a glimpse of the daily experiences of those who lived in such buildings. In fact, the commissions which generated these reports were intended to create guidelines for how to improve tenements, indicating just how poor conditions often were. Dozens of people tended to live in one building at a time, making for cramped quarters and tense situations, depending on the friendliness between residents. Most were composed of three to six floors, and cellar space was used as living quarters to maximize the number of tenants.

Flooding was common in these lower levels during periods of inclement weather. And, as one can imagine, there was often not much sunlight or ventilation - even on the upper floors, where windows usually looked out onto a narrow alley and the brick face of another building. Since electricity was not installed in most tenements, residents had to rely on what little natural light they could get, or else use candles and hearth fires to light their rooms. Bathrooms were usually a cramped space with just enough room for a toilet - per tenement, there was one for approximately every five occupants - and running water was rare for most.

In the yard, there may have been animals - the Mayor’s Tenement Commission had to prohibit keeping animals like horses, cows, and goats from being kept on tenement premises.

Unsurprisingly, these factors made tenements rather unsanitary. Diseases like tuberculosis were prevalent and spread quickly between residents, which seemed to justify negative views of tenement housing as a hotbed of crime, immorality, and sickness. Medicinal bottles would have been present in most tenements, since the choices open to wealthier Bostonians - a change of residence, diet, or a visit to the doctor - were often not available to the city’s working classes.

In fact, the poor quality of tenement housing was the result of landlords cutting corners and minimizing building costs, while housing as many people as possible for maximum income.

Still, this does not mean tenement residents did not also work to make their homes comfortable and pleasing to the eye. Mass-produced furniture was used to furnish the rooms within a tenement, made mostly of dark woods and plush fabrics. Small mementos, patterned wallpapers, framed pictures, and flowery carpets further helped to make the tenement space as cozy and homey as possible. Mismatched and likely out-of-style ceramics filled kitchens, indicating tenants’ desire to beautify their surroundings utilizing the resources available to them. Tea sets were common, speaking to the social rituals of immigrants and working-class families, and ceramic flower pots were utilized to display florals and greenery, or perhaps to grow herbs for cooking and medicines. Children’s items would have also been present - maybe homemade or porcelain dolls sat in the dark wood chairs, or a child’s tea set kept on a side table.

The consumption patterns of those living in tenement dwellings show their personalities and dreams, despite the difficulties of establishing a new life in a city with few connections and poor housing options.

Food and Family

In Boston, immigrants were encouraged to eat according to the latest understandings of food science - though 1860s ideas of what constituted “healthy” foods were far different from what we think today. The chemist Ellen H. Swallow Richards was one of the leading voices promoting foods believed to have high nutritional value at the lowest cost possible for people living in tenements, especially immigrants.

Food purchases could make up fifty percent of working-class families spending, while women’s domestic work took up the majority of their time. As the first woman accepted to study at MIT, Richards was a pioneer of sanitary engineering and took a special interest in applying scientific methods to household chores in order to improve the daily lives of all Bostonians. Beef broth, pork, baked beans, and pea soup were some of the foods on the approved list, while foods disruptive to digestion - especially spices, vegetables, and fruits - were discouraged.

In January 1890, Richards opened the New England Kitchen in Boston’s North End to provide customers with easy access to her version of health foods.

The Rumford Kitchen Leaflets, named after the version of the kitchen Richards set up at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair to educate the broader American public on healthy, economical eating, provide direct insights into how successful the Kitchen’s efforts were. Edited by Richards herself and published in 1899, the leaflets record the greatest challenge to the Kitchen’s success as the unwillingness of immigrants to give up familiar foods from their countries of origin in favor of Richards’ menu.

To some extent, Richards and her fellow workers attempted to fix their food production to meet their target clients’ needs. They included popular ingredients among the working-class including pork, despite facing criticism, and attempted to study the dietary habits of immigrants from Russia, Ireland, Germany, Italy, and beyond. Patronizing clients was forbidden, ensuring those using New England Kitchen’s services would access to both wholesome foods and education on nutrition - “but not until they are asked for.” (Rumford Kitchen Leaflets, 142)

In reality, most immigrants and working-class folks ate what was familiar, inexpensive, and convenient. Bread, butter, quickly cooked meat, and gingerbread were staples for most. In boarding houses, easy-to-prepare and serve meals were common, including corned beef and cabbage. Soups, which could be made in big batches with relatively little effort, were the most common meals in tenement housing. Chicken or pork were the central protein during a good week, while onions, turnips, and other root vegetables composed the bulk of the ingredients in scarcer times. Immigrants also opened grocery stores and restaurants to provide their ethnic communities with foods from home, creating what scholar Krishnendu Ray calls “enclave eating.” (Ray, Food in Time and Place, 215).

While projects like Richards’ might have had good intentions, they were also meant to assimilate immigrants and ensure they took care of their appearance and living spaces according to the standards of Boston’s American community. In reality, many immigrants introduced new ingredients to Boston and America at large, including olive oil, broccoli, and tomato sauce, permanently changing Bostonian food culture.

(Re)Creating the Tenement Experience

In developing a digital model of a typical Boston tenement, we relied on floor plans printed in a 1904 report from the Mayor’s Commission appointed to investigate tenement housing conditions. As can be seen, the floor plan provides the outline for our model - but deviations from its specifications were required in order to create a cohesive, workable model. Since the floor plan itself was not sketched perfectly to scale, we had to create adjustments. The final product provides an example of what a tenement apartment may have looked and felt like.

Various religious items, foods, and pieces of furniture represent the diverse inhabitants of tenement buildings. Russian Jewish, Irish and Italian Catholic, and Chinese communities carved out space in Boston and drastically changed the city’s character during the second half of the 19th century, continuing well into the mid-20th century. The Boston of today - with its vibrant Chinatown, proud Irish heritage, and culinary capital in the North End - has only come into existence rather recently.

Since this floor plan includes a water closet, it represents one of the more progressive, well-kept tenements. Unlike buildings with only a single outhouse in the yard - possibly alongside livestock and other germ-carrying items - this building would have offered a greater level of privacy and hygiene, though the small bathroom would still have been shared by all inhabitants on each floor. Still, having a flushable toilet connected to the sewer system would have been a step up from utilizing outhouses and chamber pots.

As you can see, there is no bathtub or washing facilities, so tenants would have used sinks and basins in their rooms to clean themselves and their clothing. Similarly, electricity likely would not have been installed, so tenants relied on candles, stoves, and light vents to illuminate their homes.

Without the immigrants who may have lived in a tenement like this one, Boston as the world knows it would not exist. The medicine bottles, bowls of soup and porridge, and challah bread sustained them, but also represent the changes in daily life immigrants brought to Boston. Sewing machines show the necessity for extra income whenever possible, and amplify the importance of recognizing women’s informal (and often physically challenging) work caring for children, preparing meals with restricted resources, and using any extra time to make income for their family by washing clothes, mending or sewing them, or cleaning her own and possibly others’ homes – just to name a few of the many tasks that need fulfilling.

Using the floor plan as a guide, we have created an imagined version of a South Boston tenement around the turn of the 20th century. Take a look at the apartment furnishings and decor - how do they reflect the personalities, dreams, and limitations imposed on immigrant residents?