Causes of King Philip's War

Factions

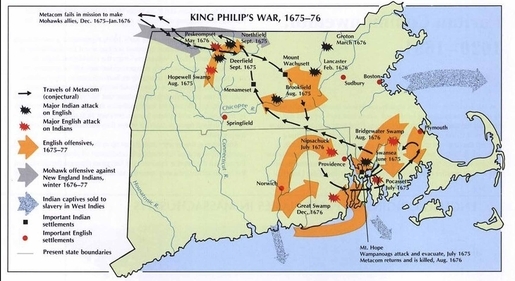

A brief overview of the King Philip’s War in Massachusetts and Maine may be helpful for students and non-specialist readers. The war was fought between two major factions: the United Colonies and Metacom’s (King Philip’s) Indian alliance. Though most of the historical actors in King Philip’s War joined one of these two factions, individual identities and allegiances were often complex. For example, some “Praying Indians” from Natick joined Metacom’s force while others served as soldiers for New England.

The United Colonies of New England was an intercolonial alliance between the four English colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth Colony, Rhode Island, and New Haven. It is important to remember that modern borders are different from those of the 1670s. One important example of this is Maine, which actually belonged to Massachusetts Bay in King Philip’s War (and until it was granted statehood and 1820)! The United Colonies were unified by their absolute distrust of Metacom’s Indian alliance, which they viewed as an Indian “rebellion” against English authority. The English almost unanimously viewed their foes as “barbarians,” and when the war broke out, the settlers usually attributed its cause to Indian “savagery” rather than their own aggression and incursions into Indian land. Despite these racist views, the several hundred “Praying Indians” from mission towns like Natick fought for the United Colonies. The Mohegans and Pequots, who were anxious to preserve their tribal autonomy in the event of Metacom’s defeat, also joined the English.1

Metacom led an alliance of Algonquian Indian tribes against the English. King Philip was a chief of the Wampanoag peoples, whose homelands include parts of modern Rhode Island, and southern Massachusetts. As discussed below, the Wampanoags had longstanding grievances against Plymouth Colony, whose colonial government had done little to stop colonists from illegally seizing their lands in the 1650s and 1660s. When war began in June 1675, Philip’s allies were the Nipmucks, Podunks, and Nashways. The powerful Narragansett tribe was initially neutral, but after a paranoid English force massacred hundreds of men, women, and children in the Great Swamp Fight of December 1675, they sided with Philip. As with the United Colonies, these tribes were not monolithic entities. Indians were drawn into Philip’s alliance by personal loyalties and family kinship networks as much as tribal allegiance. After all, wars are ultimately fought by individuals.2

King Philip also found powerful allies in the Wabanaki tribes of the Northeast (Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont). The five Wabanaki tribes were the Penobscots, the Norridgewocks, the Maliseets, the Passamaquoddies, and the Mi’kmaqs. Though the Wabanakis quickly sided with Metacom in July 1675, their objectives were different from those of the Wampanoags. The Wabanakis used the conflict to use military force to halt English colonization efforts in Maine and expand their sphere of influence by reducing English frontier towns to submission. The war’s northern theater mirrored Southern New England in its brutality, but fighting continued for another twenty months after “Praying Indian” rangers killed Metacom in August 1676. King Philip had brought the Wabanakis into his alliance against New England, but their fates were not intertwined.3

in Daniel Strock Jr., Pictoral History of King Philip's War (Boston: Horace Wentworth, 1853), 57 | Open access.

The Murder of John Sassamon

After the death of Metacom’s father Chief Massasoit in 1661, political and economic tensions arose between the English and Wampanoags. These tensions were exacerbated by colonial expansion and their dispossession of Wampanoag lands in the 1670s. On January 29, 1675, the situation exploded when Massachusett Indian John Sassamon was found dead at Assawampsett Pond in Southeastern Massachusetts. Sassamon was a Christian Indian who had been tutored by Puritan minister John Elliot, spoke fluent English, and had served as a translator for New England soldiers in the Pequot War of 1636-1637. Sassamon was one of the few Indians who was widely liked and trusted by English settlers in Plymouth Colony, and his death shocked and outraged them. Plymouth Governor Josiah Winslow and his colonial leaders wanted answers on his murder, and they blamed their neighbors the Wampanoags.4

A few weeks before his death, Sassamon had warned Governor Winslow that Metacom was mustering warriors to attack Plymouth. This warning factored into the investigation of his death. Governor Winslow initially believed that Sassamon had drowned, but they began to suspect foul play after a coroner’s examination revealed his neck had been snapped. On June 6, 1675, the first suspects were hauled into Plymouth Court. Unsurprisingly, all three suspects were Wampanoag men, who were mistrusted by both Plymouth colonists and the Massachusett Indians. Their trial lasted just two days. On June 8, a jury of twelve Englishmen and six “of the most indifferentest, gravest, and sage Indians” convicted and executed the three Wampanoags for the murder of John Sassamon. Although we will never know for certain who killed Sassamon, his case shattered the fragile peace between the English and Wampanoags.5

Copyright David Weed. Used with author's permission. This item is protected by copyright and/or related rights.

The War in Southern New England

Although Sassamon’s initial warning that King Philip intended to lead an Indian “rebellion” was probably false, the execution of his alleged murders enraged the Wampanoag sachem and his people. After about three weeks of abortive peace negotiations, Wampanoag warriors under King Philip’s direction attacked Swansea, Massachusetts on June 25, 1675. Historical actors on both sides of the conflict were soon forced to consider the extent to which their ethnic and cultural identities determined their military interests. Although Philip secured alliances with numerous Algonquian tribes across New England, many Christian Indians fought for the English. Yet the latter group was consistently distrusted by colonial leaders. By October 1675, the English had become so paranoid about the alleged “duplicity” of their allies and their intent to “rebel” that they confined them on Deer Island in Boston Harbor. Hundreds of loyal Christian Indians died of starvation in their ten months of confinement, a wartime atrocity that only reinforced how complex identities and allegiances are rarely tolerated in war.6

A few words must suffice to summarize the fighting in Southern New England. Philip’s Indian alliance achieved significant military success into February 1676, razing dozens of English towns, killing many colonists, and taking hundreds of captives. That month, Philip’s men raided sites within ten miles of Boston, and the Massachusetts Council seriously considered erecting a palisade around the city. Yet the colonists were eventually able to blunt these attacks, and a combination of increasing causalities and inadequate supplies caused several tribes to abandon their alliance with King Philip. The Wampanoags continued to fight until August 12, 1676, when Colonel Benjamin Church’s rangers tracked down and killed Philip. The English decided that Philip’s corpse should be treated as that of a “rebel,” and therefore the sachem was beheaded then drawn and quartered. His severed head was displayed for nearly a generation in Plymouth.7 In a mere eleven months, King Philip’s War fundamentally reshaped English and Native lives across New England.

“Parallel Warfare:” The Anglo-Wabanaki War in Maine

As my project’s timeline demonstrates, a very different course of events unfolded in the war between the Wabanakis and English in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont. Historians have debated whether the moniker “King Philip’s War” should be applied to the fighting in Northern New England. While there is documentary evidence that Philip sent messengers to recruit the Wabanaki tribes, this is not the main reason most Wabanakis fought the English. Rather, continued mistreatment by English settlers—which culminated in the drowning of the Wabanaki sachem Squando’s infant in June 1675—broke the fragile peace. The Wabanaki tribes fought a “parallel war” against the English. They shared similar aims with Philip’s alliance but launched entirely independent military campaigns.8 And as my timeline suggests, the outcome of the war was very different for the Wabanakis. While Philip’s coalition suffered a devastating defeat, the Wabanaki tribes were militarily victorious over the English. Their victory temporarily halted the English colonization in Maine and secured a half-century of independent sovereignty and political power in the Northeast.

Footnotes

- The following account draws from Jill Lepore, The Name of War: King Philip's War and the Origins of American Identity (New York: Vintage Books, 1998), xxv, 21- 26; Lisa Brooks, Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 122-24; and Daniel R. Mandell, King Philip’s War: Colonial Expansion, Native Resistance, and the end of Indian Sovereignty (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), 42-46.

- Mandell, King Philip’s War, esp. 90- 118; and Lepore, The Name of War, xxvii.

- Lepore, The Name of War, 21-32

- Mandell, King Philip's War, 42-46.

- Quoted from the Plymouth Colony Records, V:168, in James D. Drake, King Philip’s War: Civil War in New England, 1675-1676 (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), 71, 220-35. The identities of the six Indian jurists are unknown.

- A detailed account of the starvation of the Christian or “Praying” Indians on Deer Island is in David J. Silverman, Faith and Boundaries: Colonists, Christianity, and Community among the Wampanoag Indians of Martha’s Vineyard, 1600-1871 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 78-119.

- Lepore, The Name of War, 173-78; Mandell, King Philip’s War, 124- 27; and Douglas E. Leach, Flintlock and Tomahawk: New England in King Philip’s War (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1958), 232- 36.

- Evan Haefeli and Kevin Sweeney, Captors and Captives: The 1704 French and Indian Raid on Deerfield (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005), 185.

Further Reading

- Brooks, Lisa. Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019.

- DeLucia, Christine. Memory Lands: King Philip’s War and the Place of Violence in the Northeast. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018.

- Drake, James D. King Philip’s War: Civil War in New England, 1675-1676. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999.

- Leach, Douglas E. Flintlock and Tomahawk: New England in King Philip’s War. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1958.

- Lepore, Jill. The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998.

- Mandell, Daniel R. King Philip’s War: Colonial Expansion, Native Resistance, and the end of Indian Sovereignty. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

- Silverman, David J. This Land is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019.