Recovering Wabanaki Perspectives

Recovering Wabanaki Perspectives

Who are the Wabanaki peoples? And what was their perspective on King Philip’s War?

These questions are deceptively simple and cannot be fully addressed here. To begin to answer them, we must move beyond traditional written sources like those on the Timeline. While a handful of perceptive colonial observers (see Letter of Thomas Gardner) took the time to understand Wabanaki perspectives on King Philip’s War, these documents alone are insufficient. Instead, we must consider two alternative sources: Wabanaki folklore and material culture.

The Wabanaki Creation Story is essential to understanding the Wabanaki peoples. While this story cannot be fully historicized, it likely informed how Wabanaki peoples understood their society and relationship to their land. However, we must be careful and sensitive in using this story as a piece of historical evidence. Likewise, material culture provides an important window into the Wabanaki world but cannot truly “speak for them.” For example, the three illustrations below are intended to provide snapshots into Wabanaki life rather than be representative of their experience. But before exploring Wabanaki folklore and material culture, it is important to discuss the problematic context in which these key pieces of Wabanaki history were recovered.

Used with permission as an educational resource. Item is protected by copyright and related rights.

Combatting the Trope of the “Vanishing Indian”

The Wabanaki Creation Story is an important example of indigenous folklore, which historians increasingly recognize as a vital source for understanding indigenous peoples on their own terms. However, the collection of written and audio records of the Wabanaki Creation Story (and most other indigenous folklore) have a complicated past. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, white anthropologists and historians believed in the enduring trope of the “vanishing Indian.” Infamously introduced in James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans (1826), this trope posits that Indians are noble “savages” whose intrinsic racial and cultural inferiority doomed them to vanish “the day the white man arrived” in the New World. Canadian historian Brian Dippie observed that the Vanishing Indian trope is “a constant in American thinking” and has “achieved the status of a cultural myth.”1

Anthropologists like Frank Speck believed that the Wabanakis were going to vanish in the face of overwhelming “civilization,” and Speck recorded oral accounts of the Wabanaki Creation Story on the Penobscot reservation at Indian Island, Maine. Other anthropologists took Wabanaki items like those discussed below from tribal custody and put them into museums as relics of the past. Despite its insidious persistence, there seems to be growing awareness that the “vanishing Indian” trope is inaccurate. A 2018 nationwide study by the First Nations Development Institute and Echo Hawk Consulting found that 72% of Americans believe it is necessary to make significant changes to school curricula on Native American history and culture. Furthermore, 78% are open to hearing new indigenous narratives.2 By treating the Wabanaki peoples as historical actors rather than as passive victims or “savages,” my project responds to growing public desire for more accurate and nuanced indigenous histories.

in Charles G. Leland, Algonquin Legends of New England or Myths and Folk Lore of the Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot Tribes (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1884), 16. Open access.

The Wabanaki Creation Story

In Wabanaki folklore, the main cultural hero is Gluskap the Transformer. Gluskap was created from dust by the manitou, the origin of all cosmic power who is “in the sun, moon, stars, clouds of heaven, mountains, and even the trees…”3 Under the care of his grandmother Woodchuck, Gluskap soon became a talented hunter, fisherman, and canoe-maker.

However, Gluskap struggled with moral concepts as an adolescent. Once, he snared all the earth’s animals in his hunting sack so his grandmother would never starve. His extreme behavior displeased Woodchuck, who chided, “You have not done well, grandson. Our descendants will in the future die of starvation…You must only do what will benefit them…”4 Gluskap heeded Woodchuck and undid his sack, letting the animals scatter into the woods. In this pivotal cultural moment, he chose to act in the interests of humanity.

in Charles G. Leland, Algonquin Legends of New England or Myths and Folk Lore of the Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot Tribes (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1884), 16. Open access.

As he matured, Gluskap decided to transform Earth for human benefit. To calm strong winds, he induced Culloo, a giant magical bird, to flap its wings more gently. He stole tobacco for humans from Grasshopper, who refused to share it. And with Summer’s help, he mitigated Winter. Gluskap once encountered a village of thirsty people. They told him that the malicious bullfrog Guards-Water “forbids us water” and “is making us die with thirst.”5 Gluskap whacked Guards-Water with a birch tree and released the water. When he noticed several villagers drinking too greedily, he transformed them into lobsters, crabs, and eels. Gluskap thus created kinship bonds between humans and animals, and aquatic creatures were sometimes called “partners of a strange race.”6

in Charles G. Leland, Algonquin Legends of New England or Myths and Folk Lore of the Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot Tribes (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1884), 98. Open access.

Wabanaki Social Structures

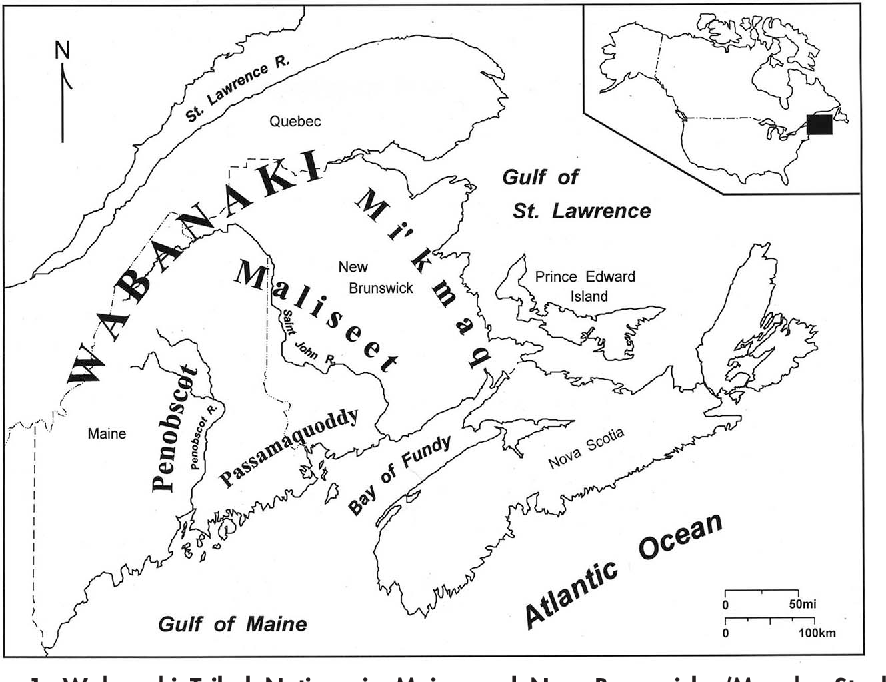

Gulskap vanished after he had transformed the world for human benefit. However, he left cultural instructions that shaped Wabanaki lifeways. Ethnologist Werner Müller observed that the “house, tent, snowshoe, sled, bark canoe, bow, arrow, lance, and knife…stem from him as does knowledge of the land of the dead, the stars and constellations, the sun, the moon, and the calendar months. In the colonial era, the Wabanakis resided in the river basins of Wabanakia [Dawnland], a homeland that included parts of Maine, New Brunswick, and Quebec.7 Their small hunting bands subsisted “on game, fish, and several fruits…” As their Creation Story suggests, the Wabanaki diet consisted of fish, shellfish, and other sea animals in the summer. In the winter, they moved inland and hunted deer, moose, and other game animals.8

Colonial and modern observers alike often confused Wabanaki tribal identities and migrations. Still, a few anthropologists and historians have tried to establish an ethnohistoric baseline for the “peoples of the dawnland.”9 In 1602, an English explorer identified twenty-two villages inhabited by perhaps 10,000 Wabanakis. However, epidemic disease decimated the Wabanaki population in the 1610s, and by 1623 their population had decreased by as much as 80%. Much like allegiances were fluid in King Philip’s War, tribal identities changed due to shifts in kinship relations brought on by disease and war. It is therefore often most helpful to think of individual Wabanakis and their relations with immediate kin, rather than using monolithic tribal labels like “the Penobscots.” As their Creation Story makes clear, the Wabanakis deeply valued kinship bonds with both the human and natural worlds.

Notes

- Brian W. Dippie, The Vanishing American: White Attitudes & U.S. Indian Policy (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1982), xi-xx, 15.

- “Research Reveals America's Attitudes about Native People and Native Issues,” Cultural Survival, June 27, 2018, https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/research-reveals-americas-attitudes-about-native-people-and-native-issues.

- The following paragraphs synthesize several accounts of Wabanaki folklore, and notes are only provided for direct quotations. Frank G. Speck, “Penobscot Tales and Religious Beliefs,” The Journal of American Folklore 48 no. 187 (1935):1-17; Joseph Nicolar, The Life and Traditions of the Red Men (Bangor: C.H. Glass, 1893), 189; and Charles Leland, The Algonquin legends of New England: or, Myths and folk lore of the Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot tribes (London: Sampson, Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1884), 14-31.

- Nicolar, The Life and Traditions of the Red Men, 189.

- Speck, “Penobscot Transformer Tales,” 39, 201.

- Kenneth Morrison, “The Mythological Sources of Wabanaki Catholicism: A Case Study of the Social History of Power,” in The Solidarity of Kin, in The Solidarity of Kin: Ethnohistory, Religious Studies, and the Algonkian-French Religious Encounter (New York: State University of New York Press, 2002), 84-85.

- Dean Snow, “Eastern Abenaki,” in Handbook of the North American Indian Volume 15, ed. Bruce Trigger (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), 137-147.

- Quoted in The Voyages of Giovanni da Verrazano, 1524-1528, ed. Lawrence Roth (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970), 140-141 in Calloway, Dawnland Encounters, 31-32.

- For the debate on early post-contact tribal ethnicities, see Bruce Bourque, “Ethnicity on the Maritime Peninsula, 1600-1759,” Ethnohistory 36 no. 3 (1989), 257-62.

Further Reading

- Axtell, James. The Invasion Within: The Contest of Cultures in Colonial North America. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Bilodeau, Christopher J. “Understanding Ritual in Colonial Wabanakia.” French Colonial History 14 (2013): 1-31.

- Leland, Charles. The Algonquin legends of New England: or, Myths and folk lore of the Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot tribes. London: Sampson, Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1884.

- Morrison, Kenneth. The Solidarity of Kin, in The Solidarity of Kin: Ethnohistory, Religious Studies, and the Algonkian-French Religious Encounter. New York: State University of New York Press, 2002.

- Salisbury, Neal. Manitou and Providence: Indians, Europeans, and the Making of New England, 1500-1643. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Speck, Frank G. “The Eastern Algonquin Wabanaki Confederacy.” American Anthropologist 17 (1915): 492-508.