Homilies

What is a homily? Generally speaking, homilies are reflections, explanations, or commentaries of the scripture read during a Mass. Whereas sermons tend to be lectures on a particular moral theme or instructions for Christian conduct, a homily aims to deepen one's understanding of the daily readings. Some of Ælfric's homilies do come across as sermons, the priest seems to focus more on ensuring that the parishioners in his congregation understand the scriptures read.

As a monk at Cerne Abbey, Ælfric wrote these homilies for other priests to deliver over the course of the liturgical year. Following the Church calendar from Christmas to Christmas, Ælfric's first homily associated with a specific Sunday is De Natale Domini (“On the Nativity of the Lord”). From here, Ælfric offers homilies for religious feast days from January to Easter on March 31, continuing on to Pentecost in May, running through the summer, until finally returning to the season of Advent beginning on December 1 in preparation for Christmas again.

Style

Ælfric's two series of homilies are marked by his plain, straightforward language. Although his Lives of Saints is famous for its rhythmic alliterative prose, here Ælfric prioritizes simple clarity over highly artificial complexity. James Hurt notes the "tendency of the prose to fall into pairs of short phrases or clauses balanced off against each other," and Ælfric achieves a level of systematic clarity as a result.[1] It seems to me that this regular syntactic style also lends the homilies to their oral delivery; such predictable, measured phrases help the listeners follow the speaker more efficiently.

In the Latin preface to the first series (not translated here), Ælfric tells his fellow priests that he has chosen to translate the Latin throughout sense-for-sense rather than word-for-word, and it seems likely that he made this decision to preserve the plainness of language he desired. When there is a foreign term that he deems important to retain, Ælfric usually glosses it immediately after. Even in a time when the liturgical readings during Mass resisted translation into the vernacular, in each of his homilies Ælfric walks through the translation of the reading line by line.

For instance, in his homily on the Lord's Prayer and the Apostle's Creed, the bishop Wulfstan offers only a translation, remarking that at the very least the people could say the words. In his own homily on the same topic, Ælfric explains the meaning of each line of the Lord's Prayer, teaching the people the importance of the words they would be reciting. Ælfric stands out as particularly attentive to the theological and even academic desires of the laity, the non-priestly members of the Church.

Content

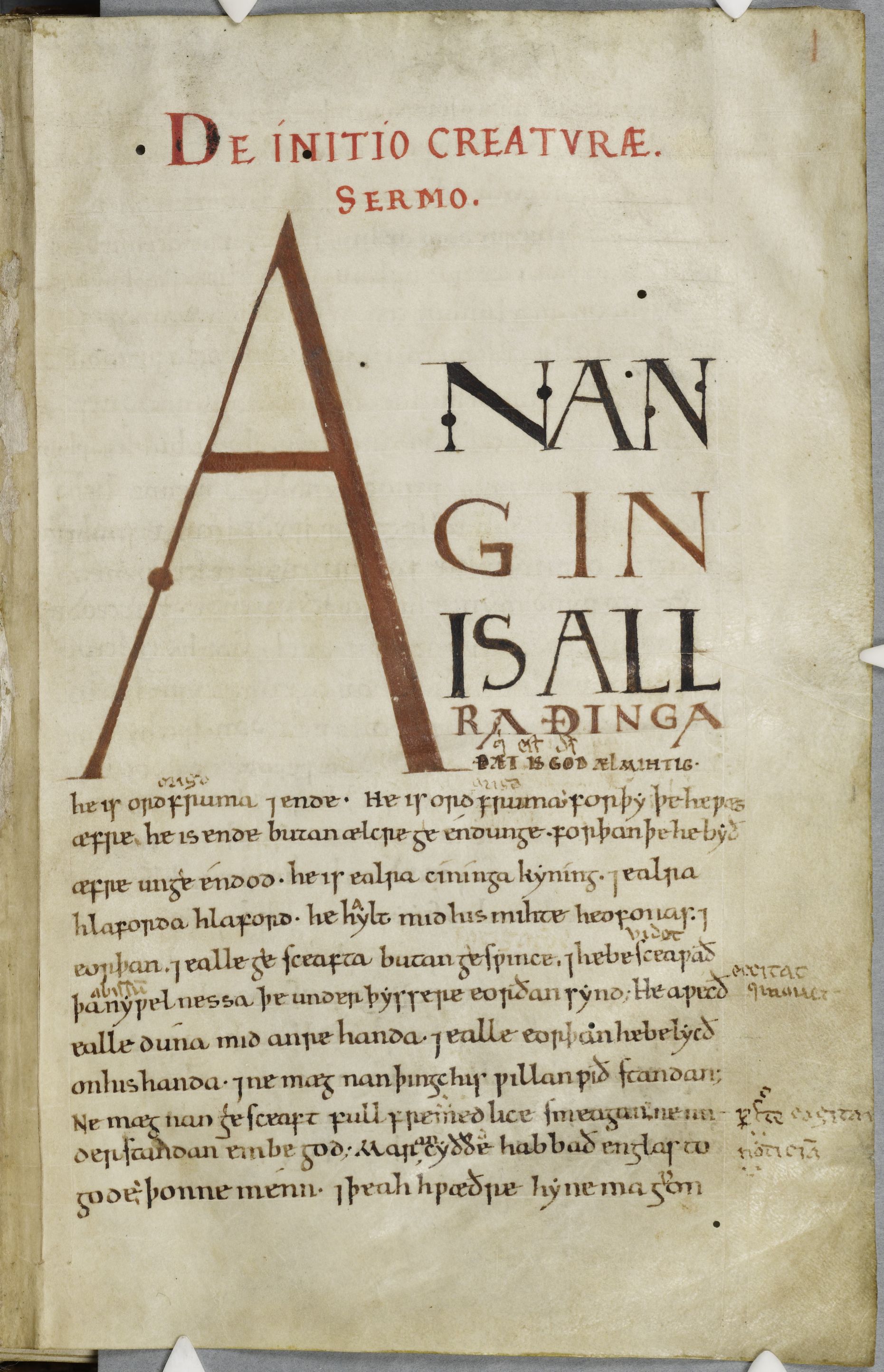

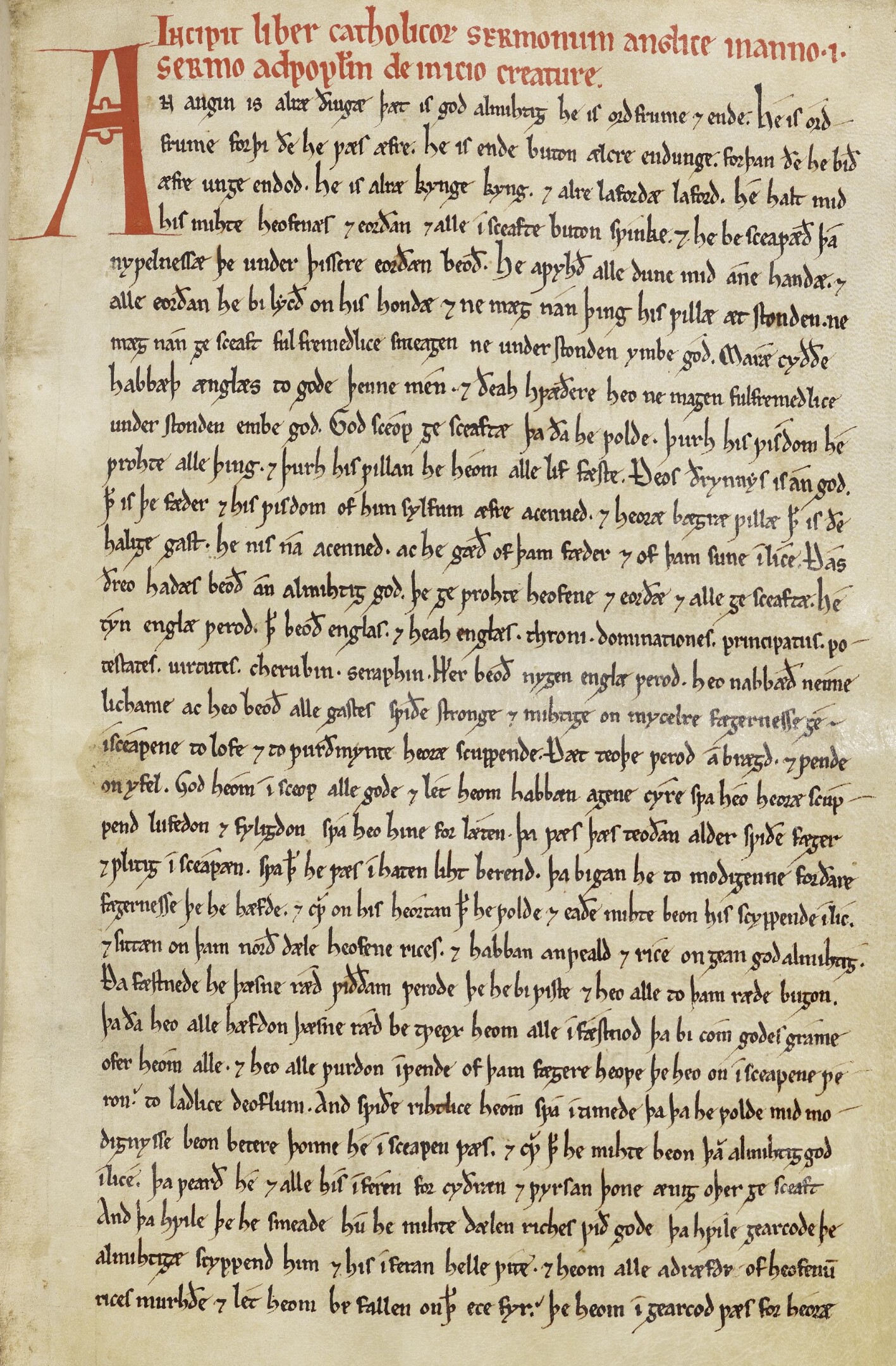

The first and second series of Catholic homilies which Ælfric wrote from 989 to 992 were designed either to be read in alternating years or to be chosen from by a priest as needed. As such, the majority of the homilies in the two series combined are associated with specific feast days throughout the year. James Hurt points out that a handful, meant to be read during the preparation period before a feast, are on specific topics such as the Lord’s Prayer. A small number of the homilies are “pendants” added to the end of other texts, and there is a single homily for a priest to offer “whenever you will” as a sort of prologue to the collection:

- Feast Days: 76 homilies

- Topical Use: 6

- Pendants: 2

- "Whenever You Will": 1 [2]

Ælfric, one of the most well-read people of his day, drew heavily from the homilies of other great Church writers for his own.[3] About a third of the homilies rely on texts by Pope Gregory the Great, while the Venerable Bede and Saint Augustine inform the bulk of the remaining homilies. Ælfric was meticulous in using sources from only such impressive authorities, because he wanted to be sure that his homilies were wholly sound and orthodox. Even with such major authors as his guide, Ælfric avoided following them to their extreme theological symbolic interpretations; he preferred to be more conservative for the sake of his audience.

Summaries

Preface

Ælfric follows his Latin preface with an Old English one too, outlining his reasons for writing this collection of homilies. After introducing himself and his patronage, Ælfric explains that he is concerned with the amount of heresy he has seen spreading, especially because he believes that they are quickly approaching the end of the world. The homilies are designed to correct these falsehoods and remind Christians of their faith, so that they may be able to resist the devil. Throughout the preface, Ælfric rhetorically emphasizes his own unworthiness for such a task, telling his readers that he can do it only through God's help.

26. June 29: The Passion of the Apostles Peter and Paul

Ælfric quickly begins by translating the Gospel into Old English, and then relays Bede's commentary on the passage. Once he has finished sharing Bede's explanation, he tells the story of the Passion of Peter and Paul. Peter, the bishop of Rome, has been competing with Simon the Magician to sway the people to their beliefs by performing miracles. When the people begin to worship Peter's God, Simon becomes the advisor to Emperor Nero. Paul is sent by God to help Peter in Rome, and together they challenge Simon before Nero. Peter and Paul are able to best Simon, but Nero has the two apostles executed in response.

August 15: The Assumption of Saint Mary the Virgin

Instead of translating a reading from the Bible, Ælfric offers a letter written by Jerome which teaches about the Saint Mary's assumption into heaven. The letter extols the virtues of Mary at length, but Ælfric hesitates to go into any greater detail because of how difficult some of the content is. He then tells two stories which demonstrate Mary's power to intercede with her Son on the people's behalf: 1) Theophilus made a deal with the devil, and Mary helped free him from it; and 2) Mary sent a protector to kill Julian the Apostate before he could destroy Basil the Great and the people with him.

November 1: Nativity of All Saints

Ælfric opens with an explanation of the importance of revering all of God's saints, even those whose names have been lost to time. He offers a brief history of the faithful, from the Old Testament patriarchs and prophets to the New Testament apostles, and then the martyrs, priests, and hermits who have followed them, concluding with a prayer to Mary in celebration of the day. Next, he provides Saint Augustine's interpretation of the Beatitudes in Matthew 5, the reading for the day. He ends this homily with a doxology to God, because of the glory of saints he celebrates.