A Reassessment

King Philip’s War (1675-78) was the most politically significant war in the seventeenth-century Northeast. Metacom (or King Philip) led the Wampanoag Indians to war with Plymouth Colony in June 1675, and soon the fighting had spread to the entire region and drawn in virtually all its inhabitants, Indian and English. Historians generally depict King Philip’s War as an archetypal “Indian War”—a conflict that ended in a costly but inevitable victory for the English, who wiped out the Indians. Colin Calloway epitomized this historical interpretation when he described King Philip’s War as “the great watershed” that triggered the momentous decline of indigenous political, economic, and military power in New England.1 Historians have accepted Calloway’s assessment as a blanket explanation for the conflict’s aftermath. Archetypical Indian Wars, after all, are ultimately Indian defeats.

But colonial archetypes conceal indigenous realities. By interpreting King Philip’s War as a classic Indian War, historians have overlooked the diverse consequences it had for Indians across the Northeast. Although the indisputably English defeated the Indians in Southern New England in August 1676, the five tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy—who call themselves “the People of the Dawn”—continued the war from their homelands in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont. Fighting continued on the northern front for twenty additional months after the English defeated King Philip. The Wampanoag leader had drawn the Wabanakis into his alliance against New England, but their fates were not intertwined.

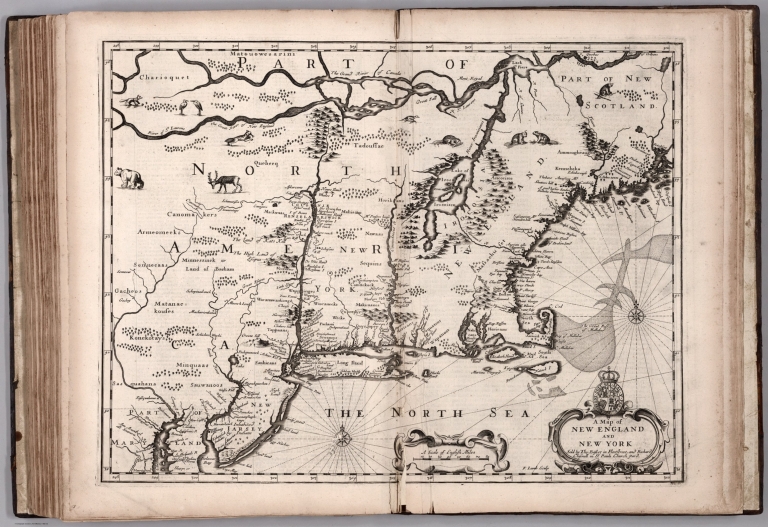

map, 1676, New York. | Public domain.

The peace treaty of April 1678 and the immediate aftermath of King Philip’s War had complex consequences for the Wabanakis. Although food scarcity forced many to seek wartime refuge at Jesuit mission villages in New France, it is evident that the Wabanakis were militarily victorious over the English. Moreover, the refugees helped forge new indigenous alliances with the Canadian Indians and French colonists. These vital new kinship networks strengthened the Wabanaki Confederacy’s political alliances in the 1680s and contributed to its military success in King William’s War (1688-99) and Queen Anne’s War (1702-13). When they agreed to a peace treaty in, the Wabanakis had done what no historian has fully acknowledged: they had won King Philip’s War.

Notes

- Colin G. Calloway, “"Introduction: Surviving the Dark Ages," 4.