Notable Bibliophiles

Meet a Subscriber

Every name in EEBS represents a member of England’s rapidly growing reading public. For some, these lists might be their only surviving imprint in the historical record. For others, it is a footnote in a well-documented life. While EEBS can be used to draw broad conclusions about early modern English society, examining the entries at the individual level can also be fruitful. Below are four examples of subscribers, notable for their presence in EEBS or their broader life.

Sir Francis Bacon, Baron Verulam and Viscount St Albans (1561–1626)

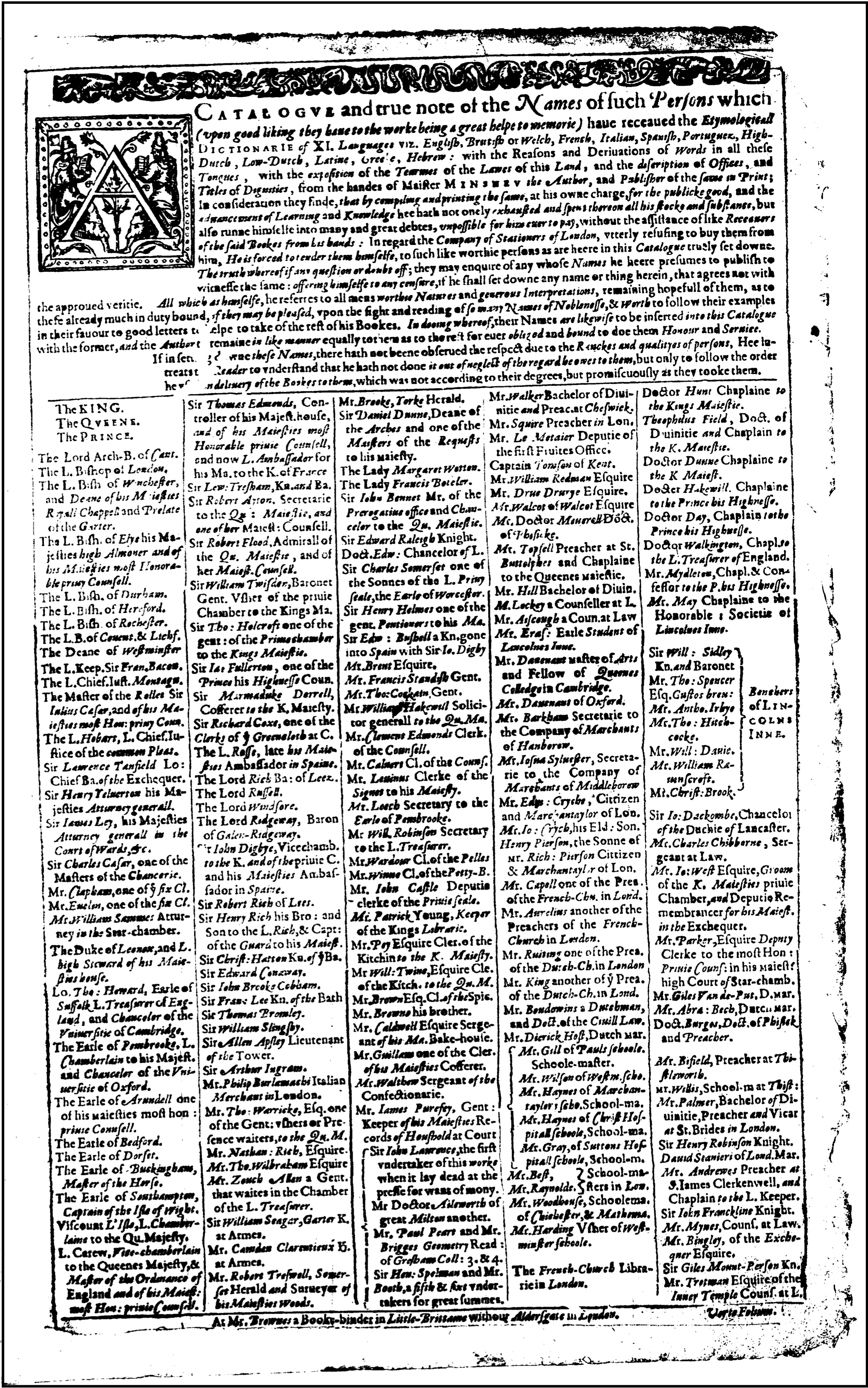

"The L. Keep. Sir Fran. Bacon." Minsheu, The Guide Into Tongues, 1617.

Today Sir Francis Bacon is best known for his brilliant scientific and philosophical writings, particularly for his defense of induction in the scientific method. He was also an accomplished politician and legal reformer. A man keenly interested in learning, who famously wrote that "knowledge itself is power," Bacon represents exactly the kind of person we would imagine subscribing to a dictionary in eleven languages: powerful, intellectual, men. The year The Guide Into Tongues was he had become Lord Keeper, the highest office in the kingdom. And yet, Bacon’s name appears alongside that of Mr. Edward Cryche, a “Cittizen and marchantaylor of Lon.” Publication by subscription could attract all kinds of subscribers, from those shaping the nation to those shaping clothes.

Sir Allen Apsley (1567-1630)

"Sir Allen Apsley Lieutenant of the Tower." Minsheu, The Guide Into Tongues, 1617.

Sir Allen Apsley’s subscription to The Guide Into Tongues is, in and of itself, unremarkable. He was a member of the gentry, working a government post in London. However, three years after its publication Apsley would have a daughter, Lucy, who would become the first English translator of Lucretius’ De rerum natura. In her memoirs, Lucy recalls her father’s encouragement of her Latin studies and her own desire to learn: “every moment I could steal from my play I would employ in any book I could find, when my own were locked up from me. After dinner and supper I still had an hour allowed me to play, and then I would steal into some hole or other to read. My father would have me learn Latin, and I was so apt that I outstripped my brothers who were at school.”1 One wonders if Lucy spent some of those hours pouring over The Guide Into Tongues, learning the Latin she would one day use to translate Lucretius.

Anne Wentworth Watson, Lady Rockingham (1627-1696)

"Honoratiss: Dō Dae An̄ae Wentworth." "Given to the most honorable Lady Anne Wentworth." (Ogilby, Virgil, 1654)

"The Honourable, Lady Rockingham, Dowager." (Moréri and Bohun, The Dictionary, 1694)

In 1654, William, Anne, and Arabella, the three surviving children of Thomas Wentworth, earl of Strafford subscribed to John Ogilby’s new translation of The Works of Virgil. Although their father had been one of the prominent men in the kingdom under Charles I, his downfall in the buildup to the Civil War ensured his children would live in relative obscurity. Anne, the eldest daughter, would marry Edward Watson, Baron of Rockingham the same year that The Works of Virgil was published. From then on she largely vanished from the historical record, although her siblings would each subscribe to Ogilby’s other translations of Homer in the 1660s. In fact, one of the few surviving references to Anne’s later life comes in 1694 when she subscribed to The Great Historical, Geographical, and Poetical Dictionary. So much had happened in England and her own life in those intervening years. Did her motivations for subscribing change too, or was the sixty-seven-year-old widow driven by the same love of learning, patronage, or prestige that may have compelled her younger self forty years before?

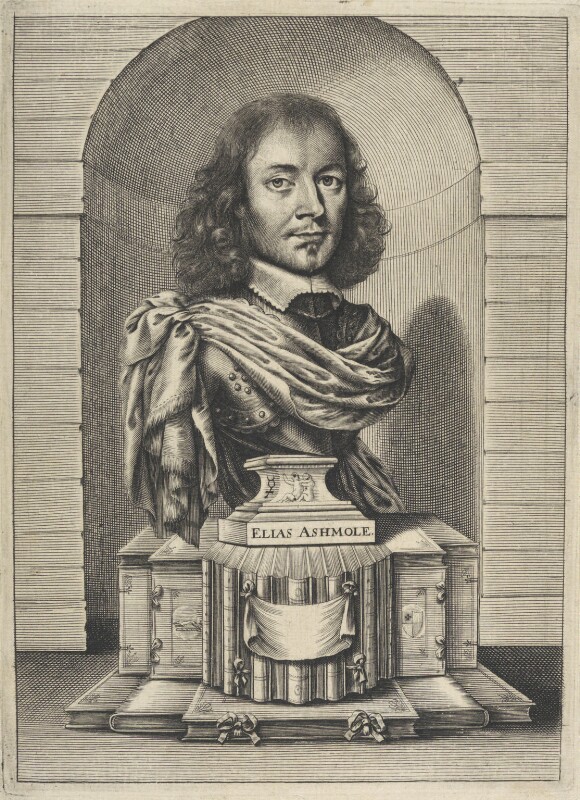

Elias Ashmole (1617-1692)

"Eliae Ashmole Arm̄ (qui est Mercurio philus Anglicus)." "To Elias Ashmole, Esq (Who is the Englishman beloved by Mercury)." Ogilby, Virgil, 1654

"Elias Ashmole, Ar. medii Templi Socius." "Elias Ashmole, Esq., a Member of the Middle Temple." Somner, Dictionarium Saxonico-Latino-Anglicum 1659.

"Eliae Ashmole Armi: Medii Templi Soci." "To Elias Ashmole, Esq: a Member of the Middle Temple." Ogilby, Iliad, 1660.

"Elias Ashmole Esq." The English Atlas, 1680.

There is a certain satisfaction in knowing that the most prolific subscriber in EEBS’s database is none other than Elias Ashmole, an astrologer, antiquary, avid collector, and founder of the Ashmolean Museum. Born the same year as England’s first instance of publication by subscription, Ashmole would subscribe to at least four books over twenty-six years. Although a fire in 1679 destroyed some of his books, it is possible that some survived to help form his museum’s initial collection. The Ashmolean, which opened in 1683, is considered the first public museum in Europe.

Notes

- Lucy Hutchinson, Memoirs of the Life of Colonel Hutchinson (London : New York: J.M. Dent; E.P. Dutton, 1913), 14. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/101687302.