AI Generated Art and the Pedagogy of Poetry

AI (Artificial Intelligence) generated art, text, and audio have emerged in the last year as potentially disruptive technologies: can students now simply plagiarize entire papers whole cloth from an internet chat tool? Is the digital art on display created by a human, or an amalgamation of digital repositories which create art in many styles in seconds? Is the audio or video clip on the screen legitimate, or a forgery produced from a provided bank of samples? Shown in this negative light, the technological advancements in AI are anathema to the traditional spirit of learning and collaboration which is key in the literature classroom. This guide attempts to invert the potentially nefarious uses of AI in education by using its inherently accessible nature to benefit students who might learn best in a visual or creative mode in the study of poetics. By experimenting with free-to-use AI art generation tools, students will come to better understand not only the function and form of poetry, but also poetic paraphrase and figurative language.

Conceptual Overview

I can’t speak for every literature department across the world, but I can speak to my own: at the beginning of the spring 2023 semester, a troubling email called for a meeting regarding ChatGPT, the new technology which could, or might someday, generate entire analytical papers from only a simple prompt. A string of text such as, ‘write an argumentative essay about Ishmael from Moby Dick that is six pages long’ could in theory generate a perfectly polished paper which would not only pass muster, but would seem thoughtful and eloquent. While in my experience the technology isn’t nearly at that stage yet, it has pervaded discourses of authorship and artistry beyond the college setting. Ammaar Reshi, for instance, undertook the challenge of creating an entire children’s picture book in a single weekend, and turned to ChatGPT for the text and Midjourney for the artwork, only cleaning up rough edges himself. The results, inevitably, were controversial (Kasulis Cho). Late last year, Jason M. Allen was briefly the subject of many op-eds for his award-winning piece “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial,” which was generated using Midjourney, drawing the ire of the other contestants and artists more broadly (Roose). To address the plagiarism issue in schools, OpenAI, the company who launched ChatGPT, announced “it ha[d] created a tool that can tell the difference between text generated by artificial intelligence (AI) and text written by a human” in early February, but this tool is still in its preliminary stages (Lonas). There are ongoing conversations about not only the ethics of such tools but also their legality in the sense that they draw on established, sometimes copyrighted, artistic or textual styles (Walsh). Currently, the publication of AI art or text for profit sits in a gray area.

However, it is very certain indeed that the technologies are continuing to advance at a rapid pace. An article titled “The Uncanny Failures of A.I.-Generated Hands,” published in The New Yorker was followed less than two weeks later by another article, “AI Image Generators Finally Figured Out Hands.” This somewhat humorous example of the pace of development aside, it is time for instructors to seriously consider the variety of paths forward, ranging from potentially including a full ban on technology in the classroom (which some instructors already include in their syllabi and account for in their pedagogy) to incorporating the more helpful applications of these new technologies which teach their responsible use into the humanities classroom without allowing plagiarism or digitally generated essays or short responses. In essence, an effective implementation of AI tools in the classroom could look like doing what we already do with existing technology when we clearly define and communicate our expectations: allowing computers for research, but not direct copy-and-pasted text from Sparknotes; allowing iPads for note-taking, but not watching basketball. Such a balanced future might use technology to “afford new teaching and learning experiences that are not possible without the technology,” not just enhancing learning, but “redefin[ing] and transform[ing]” it (Trust 54).

Inspired by Patrick Thomas Morgan’s “Let’s Get Heretical” lesson suggestion which appears in The Pocket Instructor Literature: 101 Exercises for the College Classroom, this lesson plan embodies a critical and balanced approach to new AI tools: it suggests a new way to make poetic meaning using AI art tools, particularly for students who might struggle with the conventional pedagogical approaches to often difficult poems. It is on the one hand visual and fun, but on the other, demands serious attention to not only the language of the poem on the level of the phrase, but also the ways in which poets combine phrases and lines into larger thematic wholes. This lesson plan is suitable for secondary and postsecondary students of all levels, and requires only a single smartphone, tablet, or laptop per group of students, (up to six individuals per group depending on course size and allotted class time).

The Technology

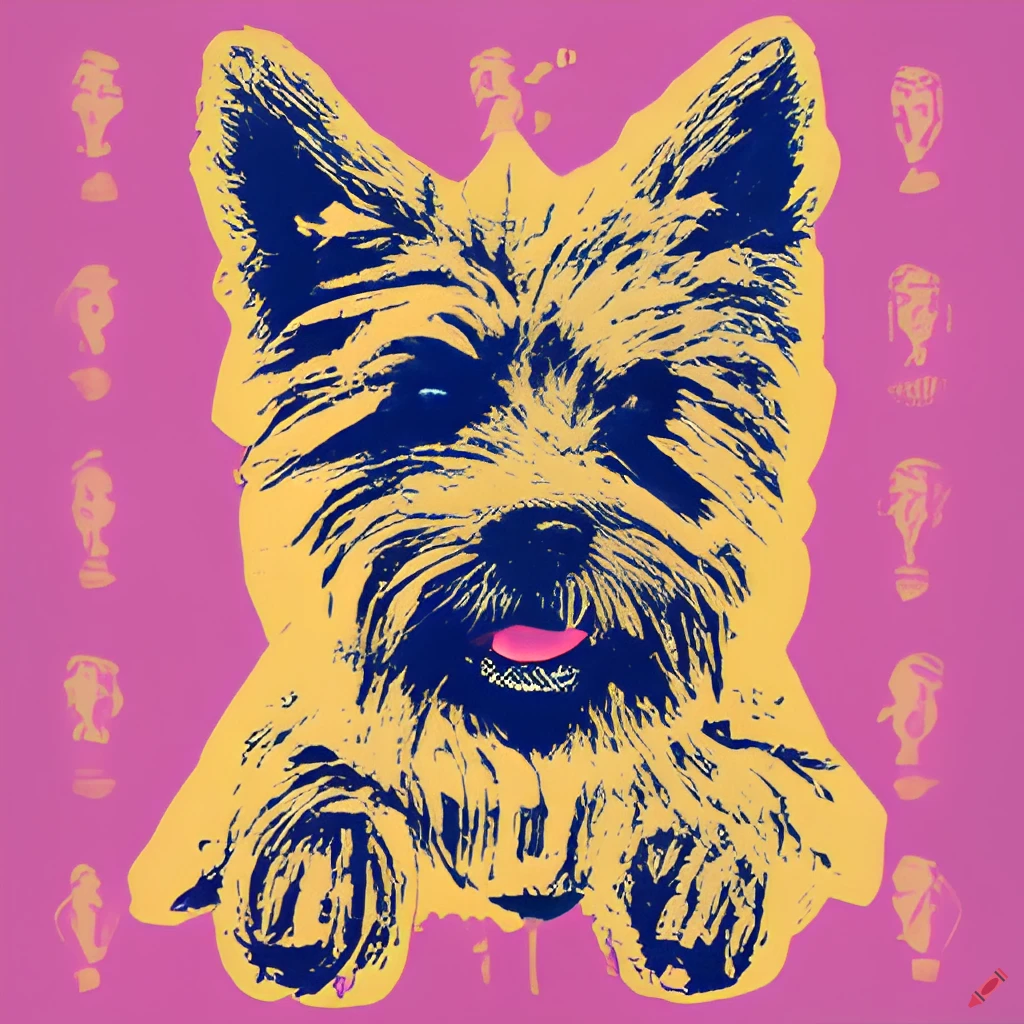

There are several different programs, with more forthcoming, that can generate art from a text prompt and which are available entirely in an internet browser and require no download. As of April 2023, some of these programs include: DALL-E 2 (requires a free account), Midjourney (extremely high quality images, but requires a free account with limited credits), Microsoft Bing’s image creator (powered by DALL-E, requires a Microsoft email account), Dream by WOMBO (phone app), and Craiyon.com, which is entirely free to use and can run on laptops, tablets, or phones. For the purposes of this lesson plan, all images will be generated from Craiyon.com, which generates nine images per prompt in approximately one to two minutes, depending on server load at the time of input. Craiyon.com developers, as of April 2023, have an Android app in addition to their browser art generator, with an iPhone app in development. Instructors who want to use some AI art component in their pedagogy are encouraged to tinker with the settings on each program to see which suits their purposes best. To demonstrate the capacity of the tool, here are a few sample images from Craiyon.com using the prompt input “Cairn Terrier in the style of [Picasso/Vermeer/Warhol]”:

With Craiyon.com, no fine tuning is necessary: the website will run with only a text prompt, and generate nine unique images each time the user presses ‘draw.’

Lesson Plan

Challenge:

Many students find it difficult to understand the nuances of poetry and poetics in comparison to prose or drama. In some cases the literal meaning of the poem may elude students entirely, or the subtlety of the images that the poetry evokes may be lost. This technology helps solve two problems: the teaching of 1) paraphrase, and 2) the use of visual imagery in poetry, because in generating images using AI tools, students will have to learn and practice paraphrase. New software has become available that can now make visual the language of poems. For students who are more visually inclined, or students who struggle with abstract metaphors or figurative language, these AI art generators can prove very useful as well as entertaining and engaging. Additionally, the images created by AI will necessarily be limited by ‘pinning down’ a specific image–the visualization will open up discussion in two ways: 1) exploring the implications of a specific concrete image in a poem, and 2) discussing the limitations of the images created, and what more the poem might suggest.

Core Questions:

- How does poetic imagery create meaning?

- How do lines of poetry combine to form meaning?

- How can we perform poetic paraphrase?

Objectives:

- Students will practice close reading the language of poetry for its content and study its form.

- Students will critically examine the use of imagery in poetic language.

- Students will generate paraphrases of poems that accurately convey imagery.

Exercise:

Before class, select one or several poems which are either particularly rich in imagery, feature potentially confusing language or syntax, or both. Some suggestions include: “Song of Myself” by Walt Whitman, “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” by William Wordsworth, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” by T.S. Eliot, “Blackberrying” by Sylvia Plath, and “At the Fishhouses” by Elizabeth Bishop. The choice of poem(s) should highlight poetic language as separate from prose, and the poem should ideally add to or cascade upon its meaning throughout. The entire lesson should take around seventy minutes, but could be shortened to fit a fifty minute session by sharing one poem as a class and limiting each group to one single image, or be divided over two class sessions.

Activity Steps:

Pre-teaching:

At either the beginning of the class session or in a previous lesson, introduce students to the agenda for the class session, the objectives of the lesson, and introduce them to the two key terms, imagery and paraphrase. You might ask students what their own preconceptions of these terms are before supplying them with your preferred definitions. Sample definitions might look like: Imagery: Language which draws upon one or more of the five senses to create a mental image or landscape in the reader. Paraphrase: Expressing the meaning of text using one’s own words rather than the writer’s words while preserving the meaning of the original text. Poetry Foundation offers a helpful glossary of many poetic terms including one on imagery, and LibGuides has a definition of paraphrase.

Class Session:

- (5 minutes) At the beginning of class, ask students to navigate to the following URL on their phone or laptop: https://www.craiyon.com/. Ask them to insert whatever prompt they’d like, and run it through the image generator at least two or three times, as each iteration generates a different result. Have them share the array of nine images with their nearby classmates: what looks strange? Can their peers guess what they inputted? Do some images look distinctly more accurate to the prompt than others? For example, the following nine images were from one single array using the prompt “robot wearing a dress painted by Matisse”:

- (10-15 minutes) Divide students into groups of 3-6 and assign each group a poem. You could assign the entire class one particularly significant poem, or let each group work on a different poem, or divide a longer poem into chunks for each group. Ask each group to identify and isolate each ‘image’ in their poem which they recognize, ranging from a phrase to a line to a stanza, depending on how the poet deploys imagery. Let them define and tinker with what, exactly, an image might look like: encourage them to divide the poem out in different ways, from small concrete images to image systems or images connected to broader themes.

- (15-20 minutes) Ask each group to generate art for several of the images which seem particularly vivid or striking, using the precise language the poet uses, including punctuation. Encourage them to use the tool multiple times to generate a series of images from the same prompt. Currently, the AI does not support or factor in line breaks within text, which represents either a possible wrinkle or potential opportunity for creativity. Have each group save strange or compelling images in a word doc or Google doc. Ask each group: what does the AI get right? Is it missing anything? How does the AI use the terms provided to generate images? What doesn’t get carried over from the words on the page to the images? These images could potentially look very abstract, but you should encourage students to critically evaluate the images against their sense of the meaning of the poet’s language.

- (10-15 minutes) Ask each group to paraphrase several of the linguistic images they identified from the poem into plain prose of their own making without poetic embellishment. Liken it to paraphrasing the plot of a novel: the components should all be there, but in as few words as possible. Building on the elements which were either lacking or seemed to confuse the AI in the previous step, ask students: after writing their paraphrases, how would each group try to create AI art that is truest to the spirit of what the poet has written? If a painter were to paint the poem from only the students’ language, how would they guide her to the best of their ability? Challenge each group to paraphrase larger chunks of the poem and generate art with entire stanzas of the original poem and their own paraphrase.

- (20-25 minutes) Bring the class back together and have each group share their art by either adding it to a communal document or emailing it to you so that you might project it on the board or post it to a class blog. Either immediately or in a following class session, have the class try to guess which images correlate to which parts of their poem, and which were generated using the poet’s language vs. the students’ paraphrase. Ask: what did each group deem essential in their paraphrase? What was the fastest element of the poem to go by the wayside? How did they approach paraphrase, and how did they come to decide what, precisely, constitutes an image in their poem?

- Suggested wrap-up: This lesson could be followed by a discussion/exit ticket/exercise in which students reflect on the following two topics, modified depending on the level and goals of the classroom: 1) Poetry: what did they learn about poetic imagery and the process of writing paraphrases from this activity? How did their understanding of both change or deepen?, 2) How did they find the process of AI art generation using self-created prompts and poetic language? What are the uses and limitations they see for AI image generation tools?

A few samples derived from the following lines of poetry, which instructors are free to use as demonstrations for their students:

“Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.”

“O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn's being,

Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead

Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing,

Yellow, and black, and pale, and hectic red,

Pestilence-stricken multitudes”

Student Feedback/Takeaways:

This lesson was tested in a secondary AP Literature classroom. Students enjoyed the opportunity to play with the art generation, as well as the chance to reimagine what reading poetry really means and how one might do it. This lesson is by no means meant to replace an entire unit of an introductory literature course, but to offer either an introduction to poetry in an accessible, novel way, or to add to already established analytical skills built using analog close reading techniques. Some students who bristled or were quiet at the mention of poetry lit up, and engaged with the text in a way that otherwise wouldn’t have been possible, while students who frequently participated in group discussions were pushed out of their comfort zones and afforded the chance to learn something new.

Works Cited

- Chayka, Kyle. “The Uncanny Failures of A.I.-Generated Hands.” The New Yorker, 10 March 2023. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/rabbit-holes/the-uncanny-failures-of-ai-generated-hands.

- “Craiyon, Ai Image Generator.” Craiyon, AI Image Generator, Craiyon LLC. www.craiyon.com.

- Fuss, Diana and William A. Gleason, editors. The Pocket Instructor Literature: 101 Exercises for the College Classroom. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Kasulis Cho, Kelly. “He made a children’s book using AI. Then came the rage.” The Washington Post, 19 January 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/01/19/ai-childrens-book-controversy-chatgpt-midjourney.

- Lonas, Lexi. “ChatGPT company announces tool to detect AI-written text amid education controversies.” The Hill, 1 February 2023. https://thehill.com/policy/technology/3839136-chatgpt-company-announces-tool-to-detect-ai-written-text-amid-education-controversies/

- Roose, Kevin. “An A.I.-Generated Picture Won an Art Prize. Artists Aren’t Happy.” The New York Times, 2 September 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/02/technology/ai-artificial-intelligence-artists.html.

- Trust, Torrey. “Why Do We Need Technology in Education?” Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education 34, no. 2 (2018): 54-55.

- Velie, Elaine. “AI Image Generators Finally Figured Out Hands.” Hyperallergic, 19 March 2023. https://hyperallergic.com/808778/ai-image-generators-finally-figured-out-hands.

- Walsh, Kit. “How We Think About Copyright and AI Art.” Electronic Frontier Foundation, 3 April 2023. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/04/how-we-think-about-copyright-and-ai-art-0.