Narrative Group Close Reading

Sample Lesson Plan III: Literature Core/Studies in Narrative Group Close Reading

Long form narratives are a staple of the literature classroom, but certain passages stand out as breathtaking examples of prose, are dramatic or suggestive in their content, or perhaps mislead or confuse readers. This lesson plan is best suited for a class that will return time and again to these passages which provide enduring discussion through many readings.

Genre of text: prose narrative

Course level: beginner to intermediate

Student difficulty: low to moderate

Teacher Preparation: low

Semester time: any time after the first several class sessions

Estimated time: at least thirty minutes, up to a full class

Learning Objectives:

- Students will learn to close read passages of longer narratives for their significance in and of themselves, but also to the larger narrative

- Students will become familiar with literary devices as they appear in long form prose including types of narration, speaker, and perspective

- Students will become comfortable thinking on their feet in ongoing conversations with their peers in a digital space as well as an ongoing class conversation

Exercise:

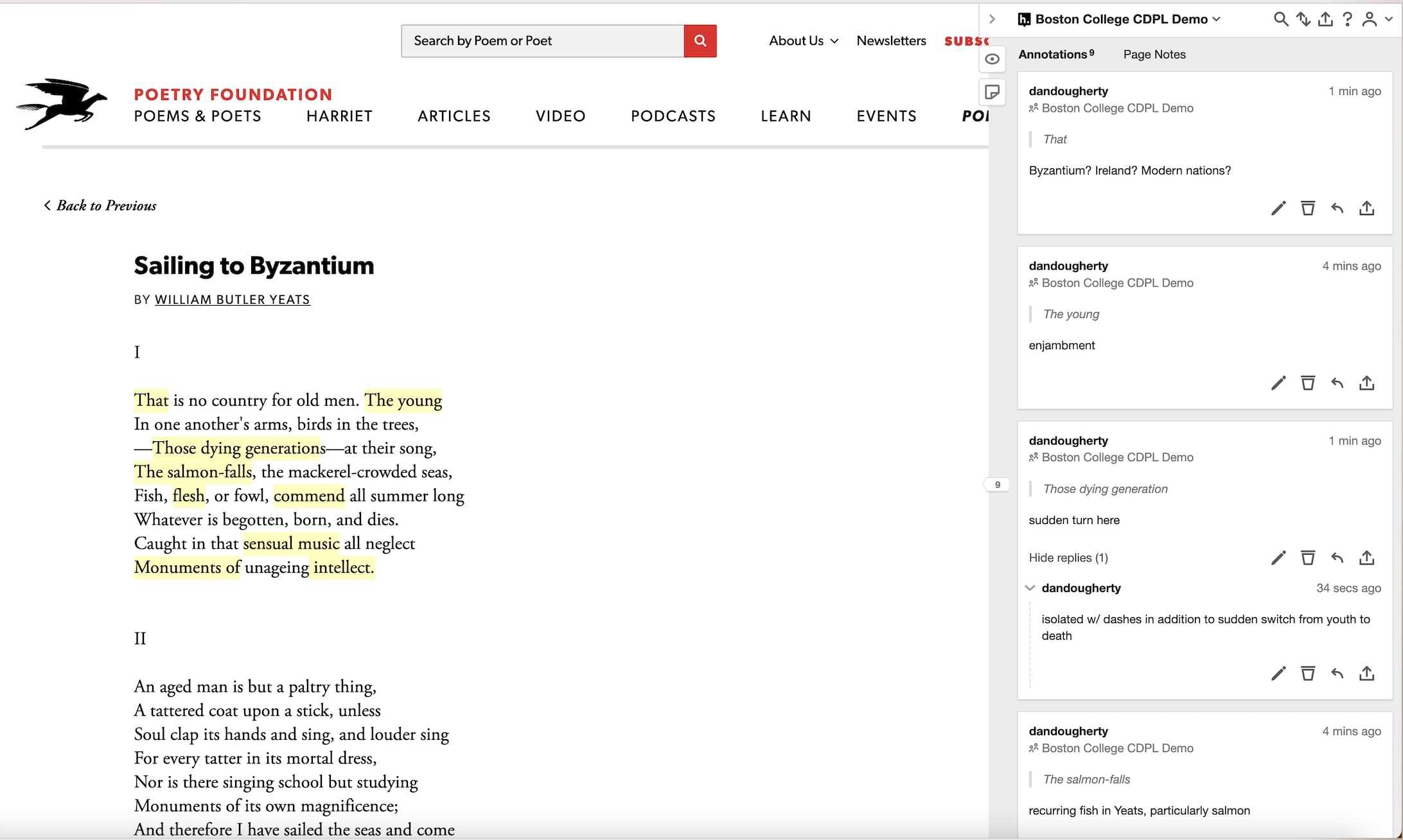

Select a passage of a novel or short story no longer than a page which is worthy of sustained discussion in some considerable way from the assigned reading. The first page of Pride and Prejudice, the first page of Chapter XXIX of Middlemarch (“But why always Dorothea?”), or one of the Big Ben passages from Mrs. Dalloway would all be suitable. Tell students that you’ll be reading the passage aloud three times, and that both during and after each repetition they’ll be asked to make or respond to an annotation for a total of six. Explain each round of annotations only in anticipation of that reading of the passage: don’t let students think too far ahead. Only when indicated may students move beyond the immediate context of the passage you’ve provided digitally. Ensure that students are aware they won’t be graded on the rightness of their annotations, and that the exercise is meant to try out new ideas and uncover new, previously unseen, components of the text.

For the first reading, ask students to annotate one element that they notice immediately about the passage. They can ask a question, or suggest an argument. They may, for example, wonder who is speaking the opening line of Pride and Prejudice, or suggest that the narrator is deliberately confusing the reader in a given sentence. After you’ve read the passage for the first time, allow students to finish their annotation and provide three minutes for them to find and respond to an annotation placed by a peer. Their responses can range from agreement/disagreement to a request for clarification, and needn’t be long.

For the second reading, ask students to annotate a stylistic element of the passage. They may find it easiest to latch onto a previous annotation, explicating it, or perhaps some new moment emerges after hearing the passage a second time. Encourage collaboration: if two or more students notice the same stylistic element, have them respond to each other, providing nuance as necessary. Again, provide three minutes after you’ve read the passage. This time, ask students to respond to an annotation of their choosing (from the first or second repetition), hypothesizing why the element appears in the form that it does. If there is a metaphor, why does the author deploy it? If the narrator addresses the reader, why does she do so? Encourage the testing of new ideas, even if they aren’t fully fleshed out.

For the third reading, ask students to make a connection of their choosing. This can be to anything outside of the text, to another moment in the text, or to another text encountered earlier in the semester. Students should feel free to pull links from outside sources, images, or multimedia content. Be comfortable with the sound of rapid typing as you read aloud: students have read the passage independently and heard you read it twice to this point.

After the third reading, ask students to respond to an annotation of their choosing by one of their peers by either adding to it or contesting it. If threaded discussions on annotations emerge, encourage students to continue replying back and forth before you bring the class back together. Allow time (five or so minutes) for students to add these final annotations as well as time for them to sift through the collective archive of annotations the class has created.

Project the annotated passage onto the board if possible, and ask students to volunteer the connections and annotations they or their peers made that stood out to them. If time permits, move slowly and sequentially through the passage. Remind students that nothing is too small to consider, and even a relatively humble looking contribution might represent something very important to understanding the passage. Additionally, remind them that the hard part–thinking of what to contribute to the class conversation on the passage–is already done.