Op-Ed with Hypothes.is

For students who may not be familiar with either digital annotations or close reading, it will be helpful to introduce them via low-stakes collaborative work. This lesson plan would be suitable for a freshman writing seminar.

Genre of text: Op-ed

Course level: beginner

Student difficulty: low to moderate

Teacher Preparation: low

Semester time: early

Estimated time: forty minutes prior to class, fifty minutes in class

Learning Objectives:

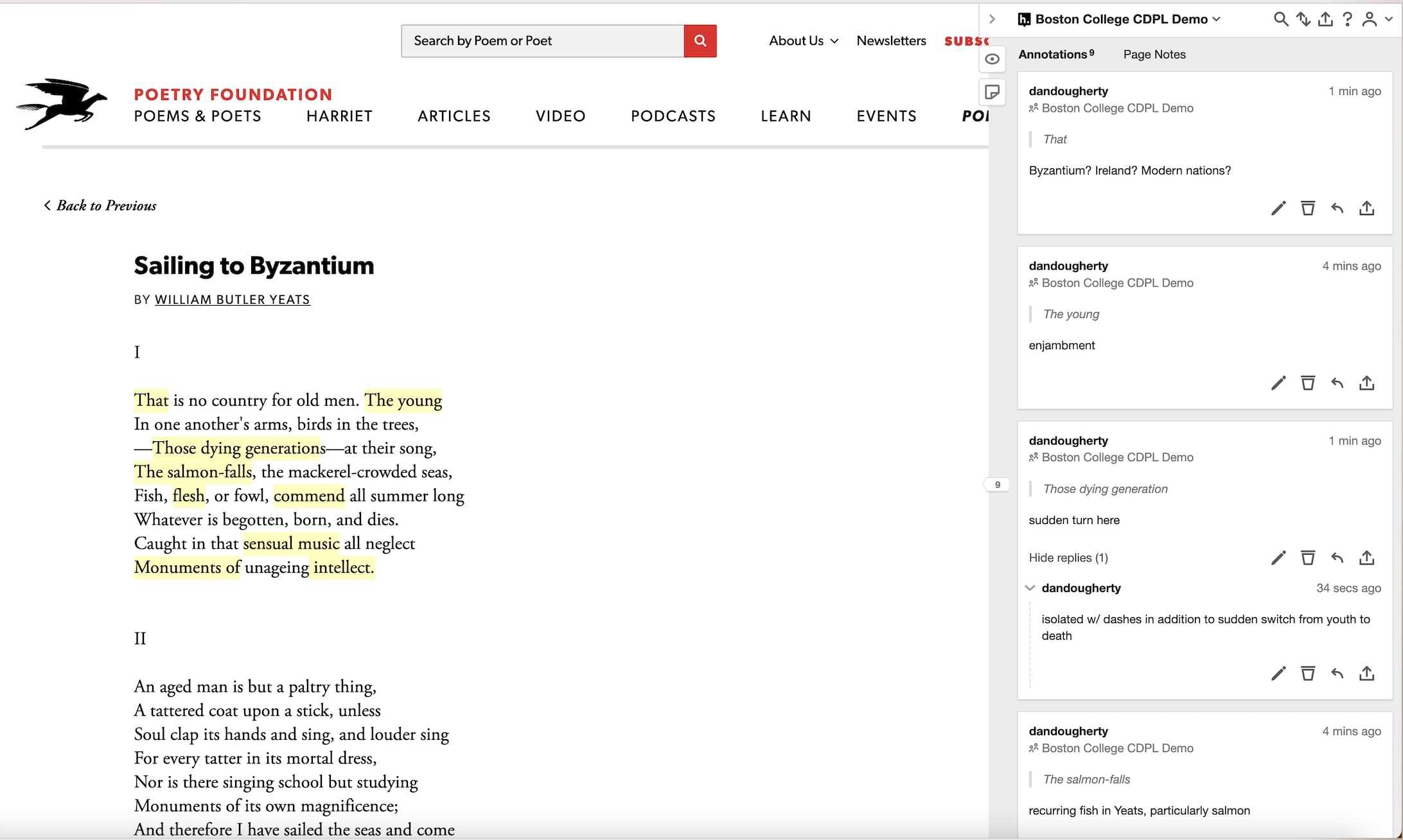

- Students will become familiar with hypothes.is annotation software (for our guide on how to use, click here)

- Students will practice the basics of close reading

- Students will develop habits of inquiry in their active reading

- Students will learn the conventions of persuasive writing

Exercise:

Divide students into groups of three to four and assign each group a recently published op-ed in the newspaper or website of your choice. Alternatively, allow students to choose their own op-ed with their small group from a list of approved sources. You may find it useful to have the op-eds relate to each other, but this isn’t necessary.

Have students sign up for hypothes.is, and send them the link for your unique class group, so all of their annotations are private within the group and accessible by both you and your peers. After assigning the articles, instruct students to complete the following tasks before the next class session in their groups:

- Read their assigned article once through without making any annotation.

- Read the article again, creating an annotation where they believe the thesis statement of the op-ed is, and paraphrasing that thesis statement in their own words. If the students can’t agree, they can mark several potential theses.

- Create an annotation after each paragraph summarizing it in a few phrases or a sentence.

- Create a note summarizing the entirety of the op-ed in a brief but comprehensive manner.

- Create a series of annotations at the points when the author uses a technique to persuade the reader towards a certain viewpoint. Students needn’t know the exact terms logos, ethos, or pathos, but you will want to tell them to be aware that the author is explicitly pushing a specific point of view.

- Annotate with question marks, exclamation points, or short phrases at particularly strange, befuddling, or amusing moments. Encourage your students to provide their own thoughts and ideas in addition to the first five tasks using the annotation tools provided.

It’s fine to let your students know that you expect a minimum number of annotations from each of them (perhaps seven or eight) prior to class. Even if some students aren’t familiar with op-eds or persuasive writing broadly construed, they should feel free to contribute summaries of sections, or point out moments of confusion. The beauty of hypothes.is is that students can add to their annotations at any time, contributing as they’d like, and you are able likewise to check in on their progress before or during class.

Beginning the next class session, your students will have op-eds they have read through several times and have marked up thoroughly. Tell them that they are now the experts of their own op-ed: later in the semester during the peer review process they will be responsible for helping their own classmates, so encouraging them to take agency in the collective knowledge-making of coursework early in the semester is helpful.

(30 minutes)

Introduce logos, ethos, and pathos formally, and offer a few simple examples of each. Then, have students break into their groups. Have each group trade their op-ed with another group, sending the url of the op-eds to each other. Now, your students will be faced with an op-ed they have not read yet, annotated by their peers. Ask them to read through the new op-ed with the annotation tab closed first, then again with their peers’ annotations visible. Ask them to do the following: Do you agree that the thesis statement the original group marked aside is the central argument of the op-ed? If not, mark another possible thesis and explain why you believe it is the core argument of the article.

At each point where the original group annotated a persuasive technique, have the current group assess it as an example of logos, ethos, or pathos, a combination of two of the three, or as something else entirely (including a non-persuasive element of the text.) Look through the miscellaneous annotations their peers made in step 6 above and expand on them. Are any of the confusing moments actually a persuasive tool? Are some particularly shocking or exciting sentences worth pulling aside for further consideration? Have each group member add annotations or respond to those that were already present with their own marginalia.

(15 minutes)

Have each pair of groups come together into one larger group. Ask them to discuss any discrepancies which came up after the second group annotated their original piece: did they disagree on the thesis, or about the manner in which the author laid out the argument generally? Were there moments which befuddled one group that the other group could explain or paraphrase? How would they change or reconfigure their op-eds to make them more persuasive, or better in another way? Finally, ask each large group to prepare for the class two sentences or short sections in each op-ed: one which uses a persuasive device or devices in a very convincing way, and another which they found weak or lacking. Encourage them to reach a consensus within the large group, even if they may disagree on certain points of the pieces.

(5 minutes)

Once each large group has reached a consensus, spend the last five minutes talking through your students’ experiences reading several op-eds, which they may have disagreed with, as well as the strong and weak moments in the argument they pulled from their pieces. Do they notice any immediate patterns, like appeals to emotion in concluding paragraphs, or the presence of data in the middle of the argument? Remind your students that in a persuasive essay of their own, you, as well as their peers, will be looking for the same cues and techniques they’ve thoroughly marked in two op-eds over the last several days. Encourage them to return to their group’s work if they feel stuck in the outline of their own essay in the coming weeks.